The Time of Listening in Chantal Akerman and Sonia Wieder-Atherton

The dialogue between Chantal Akerman and Sonia Wieder-Atherton brings image and music together in a shared time of listening.

“Time is what permits music to wound without touching.”¹

Chantal disliked superfluous words. So did Sonia. They met in that zone of silence that precedes a sound—or a frame. “With Chantal, there was no need to explain: we listened to each other in the void”, writes Sonia Wieder-Atherton.⁶ A filmmaker and a cellist: two callings that touch the same matter—time. One holds the frame still until reality gives way. The other draws the bow until sound becomes flesh. They recognised themselves in the act of restraint—in montage as in breath.

Not every artistic relation begins with a project. Some announce themselves as an echo, a vibration, an interference. So it was between Chantal Akerman and Sonia Wieder-Atherton: there was no programme to share, only a time to inhabit. A time to listen. Both were searching for something that could not be grasped directly: a breath held, a silence becoming substance, a duration that refuses completion.

Akerman always distrusted narrative. Her cinema does not tell—it holds. She edits time as one edits a threshold.² Her fixed shots are not mere images but perceptual devices, modes of experiencing temporal matter, of making it tremble. Within those images of waiting, stillness, and daily repetition, something fractures: a minimal gesture displaces meaning, an apparently neutral frame reveals an interior in tension. It is within this disposition of listening—in the possibility that the image might think, as Deleuze wrote—that the sound of Sonia Wieder-Atherton takes its place.

The cello works in a similar way: it subtracts, distils, suspends. Its music does not accompany the film; it inhabits it laterally, as a discontinuous presence. It neither explains nor supports. It moves like an autonomous body crossing through the image, leaving a faint yet necessary imprint. Roland Barthes spoke of the grain of the voice—that point where sound becomes body, flesh, eros.³ The cello, in Wieder-Atherton’s gesture, carries precisely that tactile, organic density, settling on the film like a second skin: it does not illustrate but incises. In this sense, their practices converge. Both operate on the margin—the margin of emotion, of language, of memory. And if film becomes a form of listening, music becomes a form of seeing. Time is what they both work upon, excavate, open: a time not measurable, not linear, akin to Bergson’s duration⁴—lived rather than sequential, felt rather than narrated.

Jean-Luc Nancy writes that to listen is to expose oneself. It is not a matter of receiving a sound, but of allowing oneself to be reached by what arrives. It is in this being exposed that Akerman’s cinema and Wieder-Atherton’s music meet: as vulnerable openings, —thresholds rather than answers—, as gestures that do not seek meaning but make it possible. Peter Szendy, theorist of listening, reminds us that to welcome sound is always to share a risk—the risk of being altered.⁵ Every film, every musical work, is therefore a testing ground for form and for the threshold; an alliance founded on intermittence, trust, and latency.

In Là-bas (2006), Akerman films from within a closed apartment in Tel Aviv. The outside world enters only filtered, through shutters. There is no action—only the filmmaker’s voice reflecting on identity, on exile, on her mother, survivor of the Shoah. The film is a room, a border. In that confined and trembling space, Wieder-Atherton’s cello slips in like a line of air. It does not interrupt. It does not soften. It makes the walls begin to tremble, the curtains quiver, the waiting extends. It is a sound that seeks not effect but threshold—that point which separates what may be said from what remains suspended. It does not accompany the voice, but surrounds it. It guards it.

“I tried to feel how to play what I could not see,”⁶ she writes. It is this reflected vibration, rather than any emphasis, that defines the core of their accord.

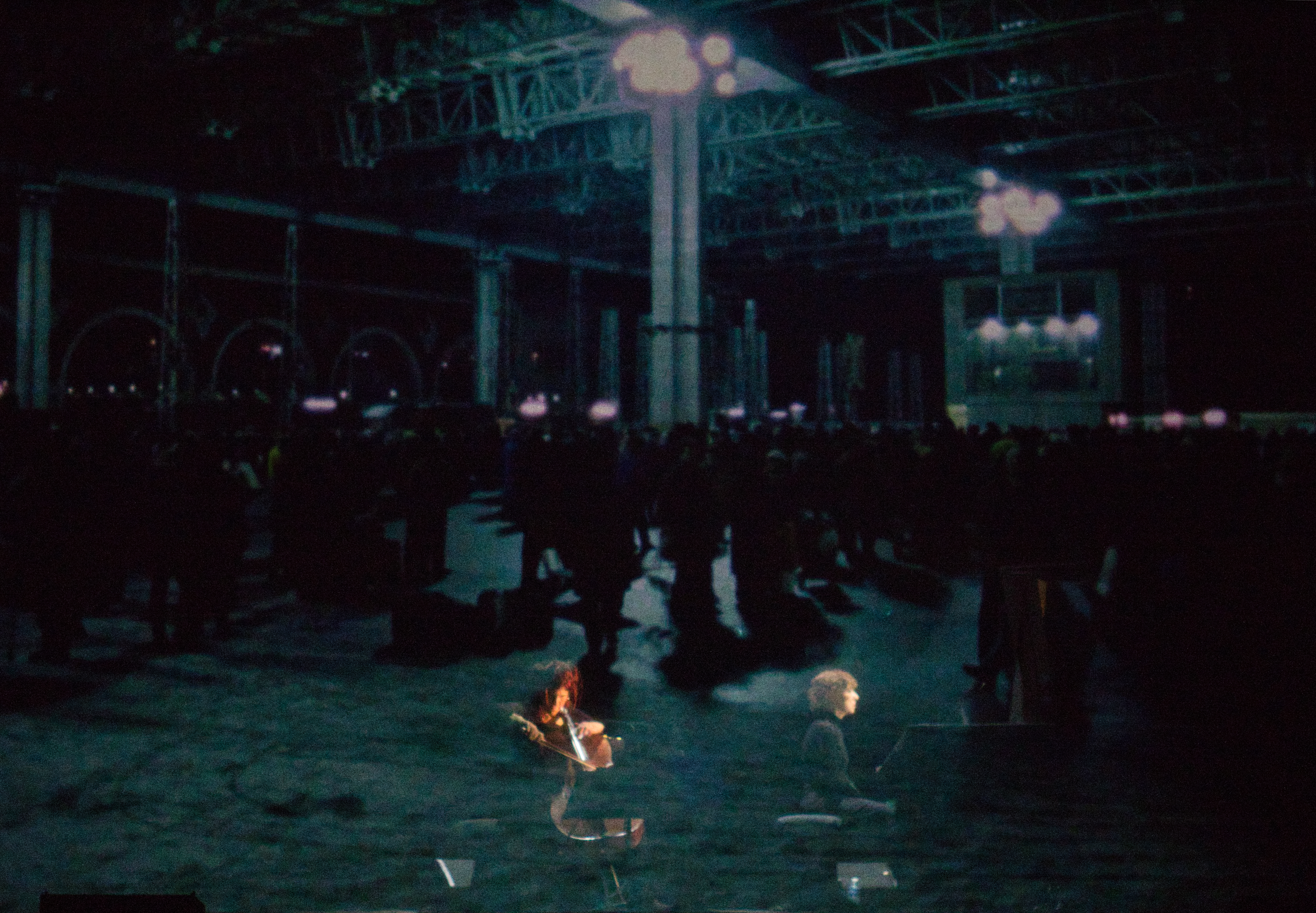

Already in D’Est en musique (2005), a concert-image conceived four-handed by Akerman and Wieder-Atherton from the film D’Est (1993), this alliance between image and sound becomes a fully formed stage device. The hybrid format—half concert, half projection, half immersive installation—puts time to the test in an even more radical way: the fixed shots and long tracking movements through Eastern Europe after the fall of the Wall are traversed by a constellation of musical pieces that, in the 2005 version, bear above all the imprint of Russian composers. Today, in the renewed version that Sonia dedicates to the project, that fabric opens into a broader “musical mosaic”, a gesture of recognition towards Ukraine and towards all the anonymous lives inhabiting those images. The score is transformed without ever renouncing the original thinking she shared with Chantal, absorbing the urgency of recent history and revealing how their common work has always interwoven—without hierarchy—art and life.

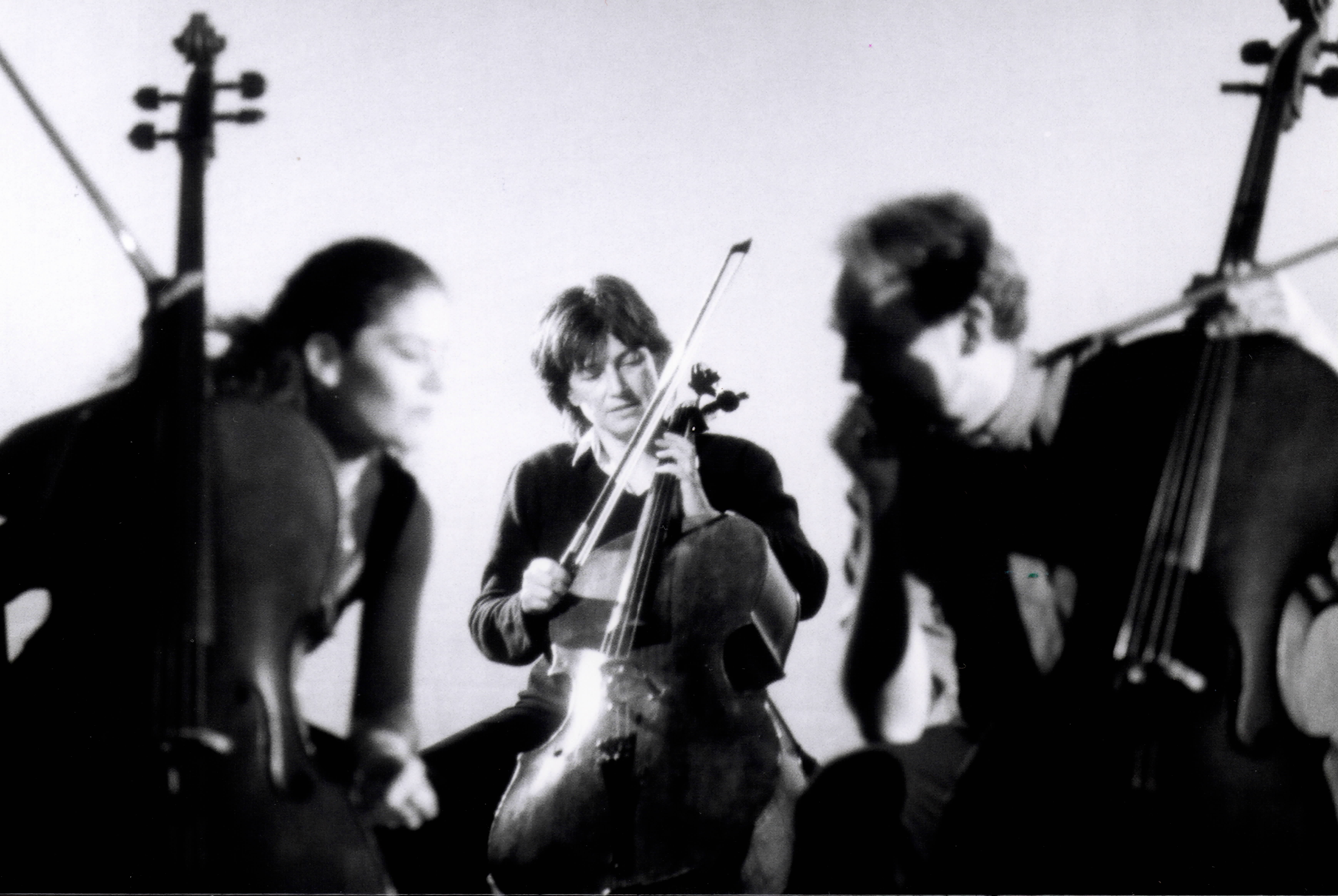

A threshold of resonance of this poetics of listening is the short film Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher (1989), in which Chantal Akerman films Sonia Wieder-Atherton performing the eponymous piece by Henri Dutilleux. Composed between 1976 and 1982, Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher was conceived as a homage to Paul Sacher, the great Swiss conductor, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday. It was Mstislav Rostropovich who imagined this constellation of works for solo cello, inviting twelve composers to write brief pieces based on a musical cryptogram derived from the name “Sacher” (S = E♭, A = A, C = C, H = B, E = E, R = D). The result was a series of dense, elliptical sound miniatures in which form obeys the mystery of sound rather than the rhetoric of composition.

Dutilleux, with his rarefied and timbrally rich style, composed three autonomous strophes bound by a shared breath: the first interrogative and inward, the second lyrical and suspended, the third more insistent, traversed by subtle tensions that seem to erode the melodic line. It is a work that does not narrate but circulates; that does not build but unravels. Akerman receives its voice with equal rigor and tenderness. There is no narrative, no drama—only the musician’s body, the bow rising, the sound surfacing—and, in the background, the echo of a daily life unfolding elsewhere, behind a window, in the light.

The camera does not accompany; it attunes itself to hearing. Each musical gesture is filmed as a perceptual phenomenon, a temporal matter that gathers within itself air, waiting, and the intensity of silence. Dutilleux’s music—so discreet and yet so exacting—finds in Akerman a filmmaker capable of offering it visible time without ever confining it. The film itself becomes a variation, not on a theme but on aural attention—an attention that turns into image. Like the composition from which it takes its title, Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher is brief only in appearance. Within its contracted duration a wider space unfolds, where sound becomes time and image becomes a site of threshold. In that condensed temporal span, cinema had already learned to listen as music does. Yet later, with Mémoires, that listening took on body, space, and presence: no longer merely an image receiving sound, but a shared time that renders it visible.

It is this quality of echo, rather than of emphasis, that defines their collaboration. In Mémoires—a concert-performance conceived in 1999 and presented in various versions in Paris, Marseille, and Jerusalem—the images Akerman entrusts to the stage are not narrative but images of the interstice: faces, hands, interior architectures. The music draws from archaic and popular sources, yet transfigures them into something other—a landscape of emotion, a stripped-down liturgy, an act of transmission not genealogical but affective. In a time dominated by reproduction and dispersion, Mémoires chooses the rare form of apparition. It is not a fixed work, but a performative space that reopens each time, like a gesture renewed through listening. Its performances—never identical, never repeated—unfolded as a constellation of fragile and intense events that crossed Europe and North America like moving vigils of sound and memory. At the Philharmonie de Paris, and in festivals such as New Horizons in Wrocław, RIDM in Montréal, or FIAF in New York, Mémoires appeared as concert, installation, silent tribute. Sometimes it preceded a film screening; at other times it replaced it, letting the music speak what the image no longer dared to show.

In 2020, with Chantal?, Wieder-Atherton transformed this practice into an itinerant homage in which sound, word, and filmic fragments intertwine like affective relics of an artistic and human alliance. In all these moments, the cello does not merely play: it inhabits the stage as an intermediate body, traversed by memories not its own, by forgotten languages, by surviving echoes. There is no concert, but presence; no repetition, but return. Each performance becomes an act of resistance against oblivion—a time of listening made hospitable, vulnerable, alive.

Particularly intense are the passages in which Wieder-Atherton works on the transcription for the cello of jewish liturgic music, orally transmitted by cantors of Eastern Europe and gathered through long research between Jerusalem and Paris, listening to oral archives, private recordings, surviving witnesses. It is a body of work that begins when Chantal Akerman asks her to compose the music for Histoires d’Amérique , wanting her cello to be “another voice” capable of joining the voices of all the film’s characters. These are not simply sonic subjects, but documents of the soul—two-faced songs that hold both joy and mourning, irony and lament. She selects songs of vigil, of exile, of childhood, in which the original voice is transposed into the cello without losing its fragility.

These pieces carry within them a broken geography: Galicia, the Warsaw Ghetto, Vilnius, Odessa. They sing of the distant beloved, of the winter that never ends, of the lost mother, of the interrupted prayer. They are lyrical forms of survival, dense with images both quotidian and cosmic. The cello then becomes voice, taking the place of the ḥazzān, transforming melody into embodied memory. The modal inflections, the micro-tonalities, the broken emission, the bow that imitates the uncertainty of the living voice—all contribute to making these pieces not recollections but presences. The music does not quote; it bears witness. And each piece is a sensitive site of the past: it does not illustrate memory, it makes it happen again.

These songs belong to an uncodified heritage where the boundaries between sacred and profane, between mourning and celebration, between language and sound, are continuously held in tension. There are lullabies for children never born, funeral laments in the form of dialogue, ballads of exile that speak of separation, forced departures, absences. It is not rare for an apparently playful melody to conceal within itself a fissure, a fracture—as though tonality itself knew what words cannot say.

Wieder-Atherton does not transcribe: she translates into the body. The bow does not accompany the song; it precedes it and follows it. Her gesture—slow, porous—restores the irregular rhythm of a voice that holds back a sob or pursues a memory. Here the cello, with its deep vibrations, reproduces the phonetic instability of Yiddish: the krekhts (breaths, sighs), the schleps (slidings), the tremors that make the voice human even when it is broken. In certain sequences of Mémoires, these melodies seem to arise not from a score but from an inner zone, as though memory were no longer contained within an archive but passing instead through the performer’s body. Thus the song is not reproduced but reactivated, and its transmission is not philological but posthumous. It is not a matter of reconstructing an origin, but of offering it a new time in which to occur.

Some pieces evoke the tradition of the nigun—the wordless spiritual chant typical of Hasidic mysticism—in which the exhausted repetition of meaningless syllables (yai dai dai, bim bom bom) aims to suspend language in order to reach a point of prelinguistic expression. Wieder-Atherton reinterprets these motifs as openings in historical time, as apertures of an archaic acoustic memory. Music becomes a mute ritual, a liminal gesture: a gesture linking what can no longer be said to what still asks to be heard. From this perspective, Mémoires is neither performance nor concert, but vigil: a place where the reverberation of effaced voices becomes a sonic presence; where the past is not illustrated but hosted; where memory is neither document nor witness, but an intermittent acoustic phenomenon—matter returning in the form of vibration, of timbre, of musical laceration.

This relationship between memory and sound is rooted as well in Wieder-Atherton’s own formation. At nineteen she left for Moscow, behind the Iron Curtain, to study with the cellist and pedagogue Natalia Chakhovskaïa at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory. In those two and a half years of apprenticeship—cold, linguistic difficulty, daily deprivation—she learned to think of the cello as a voice: the relation to the string, the pressure of the bow, the intensity of interpretation became ways of inhabiting time rather than merely executing a score. It was an initiatory journey that would continue to nourish her work, all the more after her teacher’s death and after the aggression against Ukraine, when those memories resurfaced as irreducible presences.

From this need to bear witness arose Carnets de là-bas, created with Clément Cogitore: a concert-form narrative where Sonia’s recorded or live voice reading her Soviet notebooks intertwines with “shadows of cello” she recorded herself, the cello’s song onstage, and a video montage of true and false archival images. Music by Shostakovich, Boris Tchaikovsky, Bloch, Scelsi, Schubert, Couperin, Bach, Monteverdi intersects with Cogitore’s visual “escape lines”, which respect the intimacy of the memories by selecting fragments that brush against them without ever claiming them. As with Akerman, past and present, presence and absence, document and invention recombine in a play of resonances where what matters is not chronology but the shared vibration of lived time.

In this context, music becomes an act of care and of restitution. It does not merely evoke a lost origin but opens a site of sonic perception where inheritance and fragility coexist. Akerman, with her invisible yet operative direction, does not superimpose illustrative images: she allows them to emerge, to vibrate in listening, within sound, with sound. In this way a shared gesture of affective hospitality is created, in which mourning and memory are never closed but continuously reopened. The image, in these works, is never a document; it is a survival, a return in the form of difference. As Georges Didi-Huberman writes, the image is an interval between the visible and the unseen, between the past and the present.⁷ It does not restore time: it frays it. It puts it into crisis. Akerman works with these images as with affective remains, as with relics. The music of Wieder-Atherton enters this grammar as an acoustic fissure: it becomes sonic dust, remainder, lacuna. “The images that stay with me are not visual, but acoustic,”⁶ she declares.

At times, their exchange took the form of a silent dialogue made of minute understandings, of restrained glances, of presences brushing against one another. In a recent interview, Wieder-Atherton recalled: “We never spoke about intentions. Chantal did not explain. She gave me space. Rather than telling me what she wanted, she offered me a void to inhabit.” And perhaps it is from that very void that certain inevitable questions arise for those who listen to her work today—with an attention that is not only poetic, but also technical. A void in which certain questions arise—not as interrogations to be answered, but as reflections suspended in the very space where sound is born: how the bow seems not to produce sound but to draw it out of silence; how broken, discontinuous materials like Yiddish songs or wordless chants demand to be translated into the body rather than merely performed; how tension becomes latency and latency becomes vibration.

In 2020, presenting the performance Chantal?, Wieder-Atherton described their relationship in these terms: “It was a dialogue with Chantal. With Chantal in Blow Up My City (1968). With her reading voice, her gestures, her silences, her dance at once farcical and tragic, her anxiety murmuring small motifs.” A dialogue not founded on declared intention, but on a shared availability to dwell in the interval, the listening, the latency. This mode of working—based on allusion and reciprocal attention—produced works that were not born of a predefined project but of consonance. Like two lines that never overlap but pursue one another, Akerman and Wieder-Atherton composed a score made of pauses, hints, elusive gestures.

In their shared practice, image does not illustrate music, nor does music underscore image: both withdraw from subordination, establishing a relation founded on asymmetry and trust. It is a model of collaboration in which difference is not an obstacle but a condition of resonance.

In No Home Movie (2015), a film-testament, this logic reaches its extreme. The title itself is a torsion: what remains of the home, of the mother, of the voice. A film without music. Yet it is here that music becomes flesh—a spectral flesh. Every silence is full of the sound that is missing; every fade a resonant chamber of the unsaid. The cello is silent, yet it vibrates elsewhere. The spectre of listening remains—it remains as that which we cannot cease to hear, even in the absence of sound. Akerman films her mother in the fragile everydayness of their final cohabitation. No music accompanies those images, and yet it is as if the cello had already played, and only its echo endures. Every dissolve, every waiting, every disturbed pixel is already sound—a vanished sound, still vibrating. “Every sound I produce addresses an image that is no longer there. Or perhaps never was,”⁶ Wieder-Atherton recounts.

In their work, silence is not empty. It is made of words unspoken—a dense, invisible substance seeking a form. In Alexis, or the Treatise on the Vain Struggle, Marguerite Yourcenar writes that every silence is woven of words not said. And she adds, with sorrowful lucidity, that perhaps this is why one becomes a musician: because someone must speak, not with words—always too precise not to wound—but simply with music.

Music, in this sense, is not ornament but necessity: a gesture to give voice to the unspeakable, to let silence speak without violating it. Akerman and Wieder-Atherton share the ethics of an art that does not display, but safeguards. They never told a story. They practiced a space. They inhabited the interval.

And precisely in that suspended interval, they taught us to listen to the time that remains—not measurable time, but that which insinuates itself among the folds of waiting, of loss, of memory. “Playing was a way of holding the image, of not letting it disappear entirely,”⁶ as if each note could build a fragile dam against oblivion, as if sound, more than words, had the power to keep what is no longer visible.

Maurice Blanchot wrote that “the essential word is the one uttered when there is nothing left to say,”⁹ pointing perhaps to that extreme threshold where language no longer explains, but remains—where it bears witness to a fragile yet necessary presence.

The work of Akerman and Wieder-Atherton is made of such silent words, of chords without emphasis, of gestures that persist even when all else is still. Sonia’s music did not accompany Chantal’s images; it inhabited them, like a breath held. Every note was a thread of absence—drawn from time, from exile, from nostalgia—woven between an abandoned room and a passing train.

Chantal was the immobile frame; Sonia, the vibration that remains.

Not to fill the silence, but to let it bloom.

To let it breathe.

As if the bow remembered.

As if the cello were still searching for her.

I am deeply grateful to Sonia Wieder-Atherton for the generosity with which she has shared memories, words, and music that continue to resonate through time. Her voice, embodied in sound, has made this act of listening possible. My heartfelt thanks also go to the Chantal Akerman Foundation for kindly sharing the images and for their visual and symbolic stewardship of a body of work that continues to question our present.

1) Jean-Luc Nancy (2007) Listening, trans. Charlotte Mandell. New York: Fordham University Press, p. 11. (Orig. Fr. À l’écoute, Paris: Galilée, 2002, p. 16.)

2)Gilles Deleuze (1989) Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

3)Roland Barthes (1977) Image, Music, Text. London: Fontana Press.

4)Henri Bergson (1910) Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. London: George Allen & Unwin.

5)Peter Szendy (2008) Listen: A History of Our Ears. New York: Fordham University Press.

6)Sonia Wieder-Atherton, quoted in interviews and programme notes for Mémoires (1999–2020).

7)Georges Didi-Huberman (2005) Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art. University Park: Penn State University Press.

8)Marguerite Yourcenar (1984) Alexis, or the Treatise on the Vain Struggle. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

9)Maurice Blanchot (1982) The Space of Literature. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

December 23, 2025