Sanam Khatibi, from objects to order

Brussels-based artist Sanam Khatibi’s collection of objects is a fundamental part of her artistic practice. An analysis of her act of hoarding shows why she is not but an another example of the artist as collector.

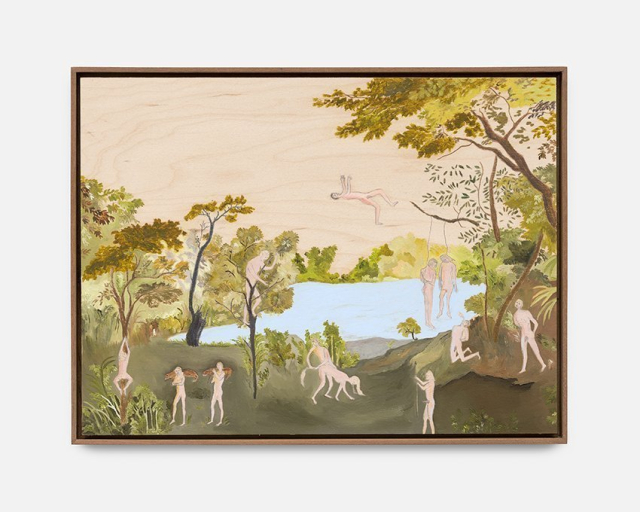

Sanam Khatibi, Songs From the Cold Seas, 2018, oil, pastel and pencil on panel. Courtesy of Galerie Rodolphe Janssen.

Two big bookcases impress those who enter the house/studio of artist Sanam Khatibi for the first time. About 3 meters tall and not larger than half a meter, these two pillar-like pieces of furniture frame the kitchen entrance and are — somewhat literally — a collection of small art exhibitions, or small installations to be precise. Each one of their shelves, with their dimmed warm back-light, bear a different display of objects from the large and highly variegated collection of the artist. For example, the third shelf on the right bookcase contains nothing less than a vintage Japanese wooden tea box, a terracotta statue of a bird goddess from Syria dated 3-4 century BC, a mechanical crocodile toy that can walk, an African voodoo statue of two bound lovers, a flea market painting of a church, possibly from South America.

Objects from Sanam Khatibi’s collection. Photograph by Gabriela De Clercq.

The act of hoarding objects is hardly rare in the case of artists. From Warhol’s tin toys and cookie jars, to LeWitt’s music scores, it seems that collecting third party artefacts is a fruitful activity for the creative mind, an activity documented even by large exhibitions in important institutions. The case of Sanam Khatibi is however more than another instance of the artist as collector.

Sanam Khatibi’s order.

First of all, her collection is eclectic to say the least. Adding to the shelf mentioned above, one cannot but feel amazed when considering a hoard containing things such as a vintage castle toy from the Masters of Universe cartoon, Chinese pottery, Persian rugs, Oriental sex figurines, and assemblages of artwork found on Pinterest. Hence, contrary to the obsession for a precise series as in the case of Warhol or LeWitt, Khatibi’s attitude comes across as more encompassing. She told us that there is a certain chaos in what she owns — how can a 1980s vintage toy be kept together with a Persian rug — yet a chaos that is navigated through her subjective ordering of it.

Secondly, even though the hoarding of objects from a plethora of sources, and the activation of their display together through a stroke of serendipity, are quintessential post-modern dears (for example, let us recall the postmodern interest in Aby Warburg’s or André Malreaux’s process of association in photo panels and books respectively), there is a different twist in Khatibi’s work insofar as she includes her own artworks and artefacts in the displays of her collection, as though the coherence of an installation would require her to fill in the gaps when third party objects cannot do so. For an example of this process, we can mention some ceramic tongues and ears made by Khatibi for a specific set up of otherwise very different items from her collection.

And perhaps even more importantly, Khatibi’s objects fruitfully wind up in her artwork too, which is not always the case for artists that collect. Along the human or animal figures, active in ritualistic, violent, or sexual acts (according to many, the signature topics of her paintings), there exist a number of painted objects that are directly inspired, or literally taken from her collection—see for example a Persian brass pot she owns, depicted standing next to a woman in her painting Empire of the birds (2017), which was shown next to the actual object in a 2017 exhibition at Rodolphe Janssen’s gallery in Brussels. Likewise, her Renaissance-inspired representation of natural landscape is often completed with details of curiosities from her own cabinet.

Sanam Khatibi, Empire of the Birds, 2017, oil on canvas, and original pot from her collection.

In respect to already mentioned Malraux’s assemblages of Musée Imaginaire, Anna-Sophie Springer claims that no objectivity and scientifically sound analysis of figures and forms is present, but rather an aesthetic act of juxtaposing things. We can similarly speculate that no scientific mindset is what drives Khatibi’s installations and use of her objects in artworks, and no scientific investigation — for example via psychology or even psychoanalysis — is necessary to read through them either. It is instead a matter of aesthetic making and experiencing of these “displaying constellations”, to take Springer’s metaphor for Malraux’s assemblages. Or to use Mary Ellen Solt’s 1968 taxonomy of concrete poets, Khatibi’s installations are more about the intuitive arrangement of materials typical of the expressionists rather than the systematic/schematic approach of the constructivists.

Sanam Khatibi relationship with words.

To strengthen this argument, it seems important to mention the way Khatibi titles her artworks. She told us about an archive of both personal and found sentences inspired by the books and other text-based materials she collects. Once an artwork is finished, one of these sentences is picked up by either her or her friends to become the title. In this way, the process of intuitively and aesthetically referencing or displaying objects is extended to giving names to the artworks, showing little concern for a rational and systematic approach to the piece/title coupling. In fact, even when an entire exhibition has a rather specific narration attached to it (for example the story of The Murders of the Green River in the recent exhibit of paintings at Rodolphe Janssen Gallery), her approach is far from a scientific and factual joining of it with the artworks. In this regard, the story of the murders works as a further item she came across in her collection, which ends up as part of an installation at large.

Discussing about what it means for an artist or curator to work in close contact with libraries, Megan Shaw Prelinger claims that creative and intellectual work flows from physical engagement with the landscape, where landscape is to be understood both literally and metaphorically. Khatibi’s artwork expands on this point to a different degree: her landscape of collected objects is used as material for her artwork, her artwork completes her landscape of collected objects, and the landscape of collected objects also includes text-based items such as stories and titles.

Artist’s bio.

Sanam Khatibi is an artist based in Brussels. She has featured in exhibitions around the world, including group exhibitions in Paris, Florence, Los Angeles, Mexico City, New York, Marseille, Vienna, and Warsaw, among others. Recent solo exhibitions include Rivers in your Mouth at Rodolphe Janssen (Brussels), No church in the Wild at The Cabin (L.A.), and Ask Me Nicely at trampoline (Antwerp). Recent institutional shows include Mademoiselle at the Regional Centre of Contemporary Art of Occitan, in Sète; Quel Amour!? at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Marseille; and The Biennial of Painting, at the Museum of Deinze, in Deinze (Be). Her upcoming solo exhibitions include an institutional solo show De ta Salive qui Mord at BPS22 in Charleroi (Be) in June 2019, as well as a solo show at P.P.O.W in New York (October 2019). Her current solo show, The Murders of the Green River, is on view at Rodolphe Janssen till 23 February 2019.

February 1, 2019