Disclosure & Disbelief: Kaloki Nyamai at the Stellenbosch Triennale

Kaloki Nyamai hits a nerve at the Stellenbosch Triennale with his provocative installation about about race, false borders and shared resources.

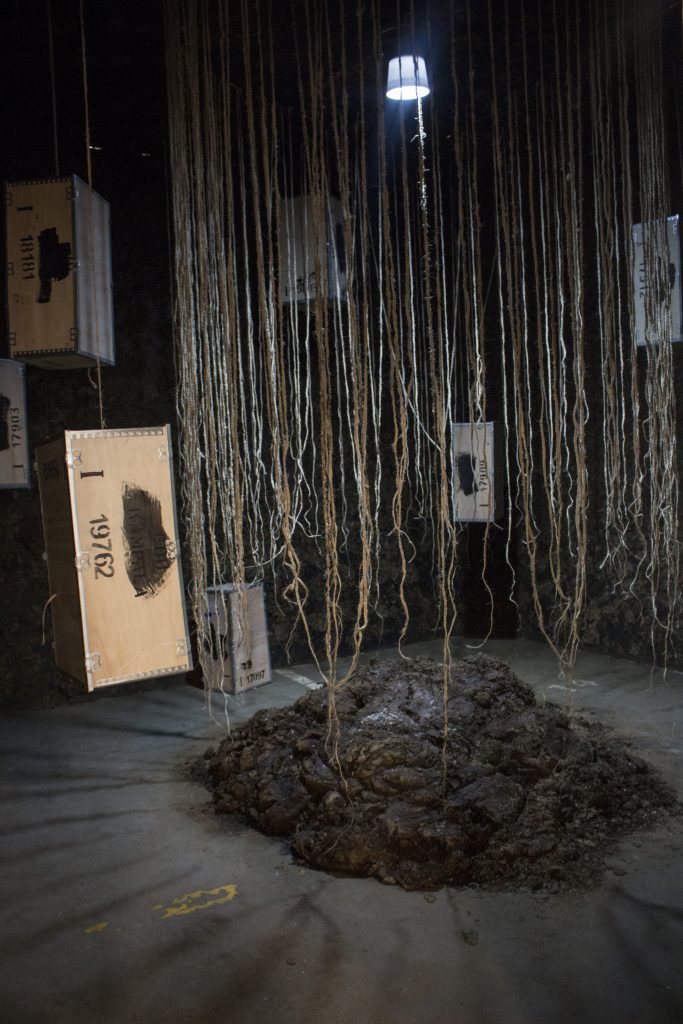

A mound of manure decomposes in a small, dim-lit room. Not necessarily what one expects to find at such a grand exhibition, but cow dung is in fact inviting the spotlight at the inaugural Stellenbosch Triennale 2020 (ST2020) as Kenyan artist Kaloki Nyamai makes his point about racial discrimination in South Africa: this shit is real.

Addressing his very strange welcome to Stellenbosch, Kaloki Nyamai abandoned his original concept for the Curator’s Exhibition, creating a new installation to convey his disbelief regarding the racial undercurrents that endure but are subtly and consistently swept under the rug. Multiple inhospitable encounters in the small town have fuelled a provocative installation about indoctrination, power and capitalism.

For many, racism is an exhausted topic. To self-preserve, it is easier to look forward, to confine oneself to comfort zones, and even to ignore discrimination where possible. But while fatigue and evasion are understandable reactions to longstanding suffering, racial incongruities persevere, and pain prevails. Of the many platforms for negotiating social injustice, art effectively explores the arduous topic of prolonged intolerances in a country where apartheid is allegedly dead. Artists can rouse curiosity and revisit critical conversations that others shy from.

Kaloki Nyamai’s latest installation at the Stellenbosch Triennale, Your Comfort Is My Discomfort, constitutes a heap of cow dung in the center of a cubic structure. Manure is splattered against the walls of the room fostering a dark space with diffused lighting. Microorganisms have begun to grow from the drying slurry but surprisingly, the smell of excrement is relatively faint. More hazardous than the brown muck are the wooden boxes, ten of them hanging at varying heights, disrupting free movement in the space. From the Bank of Uganda (BOU), the boxes were made to transport cash. The same kind of sisal used to suspend them from the ceiling also dangles freely, creating an aura above the mass of manure. A large, untitled, abstract painting, created in the same vein as his most recent paintings, hangs on the left exterior wall.

Unravelling his allegory, Kaloki Nyamai’s space is intentionally uncomfortable. The dung is an eyesore but also the edges of the rotating boxes are sharp, piercing, perilous. He has recreated the feeling of discomfort he experienced while exploring his new environment. Although the organizers of the Stellenbosch Triennale were considerate, compassionate hosts, going the extra mile to ensure that participating artists were comfortable, they could not change the social infrastructure in public spaces.

“They were really helpful – says Kaloki Nyamai. They knew how difficult it might be for us and went out of their way to allocate comfortable lodgings and healthy environment onsite. But there are of course things that were out of their hands”.

There are things the heart knows that words cannot tell; the feelings of love for example, or the feeling of being unwanted and unwelcome. Selected from over 200 artists for a high-ranking event, Kaloki Nyamai was not expecting an anticlimax so shortly after his arrival. He struggles to explain. He hoped for the same courtesies he has experienced in London or Paris. Sightseeing in Stellenbosch, he frequently felt like the other and couldn’t help but attribute this to his skin colour: black. He explains that while there are those who will argue that he pulled the race card unnecessarily or too soon, or that he read too much in to the indifference of strangers, others will nod knowingly. They understand. There is a lingering unspoken divide. It is absolute.

There has been a lot of positive social change in South Africa, and everyone is allowed at the same places, but that doesn’t mean everyone is welcome. While outwardly, there are no rules of permission, there are silent sanctions in different spaces. They are implicit. Even when no one is physically forced out, their company is unsolicited. But a reaction does not have to be violent to be inappropriate. Kaloki Nyamai’s subject matter deals with the grey zones of racism; with issues not easily demonstrable, and situations that are tough to put into words. He describes the disdainful look in the eye of a passer-by; the detachment and fear, “on the faces of some people I cross paths with.” Partialities and predispositions do not have to be explicit to have an impact – to wound, to offend, to enrage.

Despite the negative repercussions, Kaloki Nyamai daringly shares the subtle injustices he experiences, calling attention to the unsociable ambience at certain restaurants or the barking dogs and frightened children as he walks down the street. “Is it engrained?” He asks.

“Apparently, things are better now in South Africa, but as an artist who travels regularly, and without issues, this was a new feeling for me, stronger than I’ve felt before. I can’t speak for others, just my own experience”.

Kaloki Nyamai regularly uses his art to juxtapose his heritage and his current lifestyle. He often describes this self-focus as selfish. “It is about my race, my skin tone and how I feel in different environments, while observing the racial dynamics.” His investigations fit seamlessly in to the larger Triennale theme ‘Tomorrow There Will Be More of Us’, and the underlying conversations about sharing and belonging.

Discussing the theme of Stellenbosch Triennale 2020, Chief Curator Khanyisile Mbongwa referred to a newness of things, “a course correction,” using art as weaponry. Is the restructuring she alludes to about black representation? Does the “us” refer to black artists fostering visibility? The theme is vague, open to interpretation. The us could refer to those questioning the futile norms of an ailing society, or to those who refute invisible boundaries and nationalism. Mbongwa’s theme is abstract but she does refer to the tightening of borders and, as a result, her audience may be inclined to believe that she is alluding to xenophobia, to bigotry, to colour. One intuitively deduces that the subject matter of a lot of the artwork at the ST2020 is about race and exclusion.

While Mbongwa’s approach to the theme is refined and powerful, with plenty to read between the lines, Kaloki Nyamai exercises much less restraint. His installation at the Stellenbosch Triennale 2020 confronts racial inequality head on, bulldozing us with his dangerous and foul-smelling truths.

Further deconstructing Your Comfort Is My Discomfort, the reason for Kaloki Nyamai’s BOU money boxes becomes evident. He is commenting on the racial-economic discrepancies he observed in Stellenbosch. What alarmed Nyamai more than the standoffishness he experienced personally was the power hierarchy in Stellenbosch.

“I noticed the white people are extremely wealthy, not just well-off but like super rich, and many of the black people, who live on the fringes of white society, work hard for them. They are poor, very poor. There is no middle class and people are blind to just how severe the inequality is. Many people just don’t want to see it, you know. It is really strange man”.

The cash boxes appear to represent the authority that the moneyed have over the underprivileged. Using fear to impose control, the affluent curb the upward mobility of the poor, and maintain the status quo.

Probing deeper into Kaloki Nyamai’s narrative, he transcends the racial dynamics, and even the circumstances around his own blackness, as he begins to investigate a longstanding battle for power and control. Exploring the land controversy in Stellenbosch, he realizes that it is not just about color but about a resistance to change. In the clash for resources, who will part with what they have, share, redistribute assets without a war? Observing the unyielding disparity between the rich and the poor, Nyamai acknowledges that these circumstances are not limited to South Africa. They exist everywhere. Exploring the link between colour, class and control, he isolates the problem: “Instead of fighting capitalism, we are fighting race.” Urging us to shift focus, he pinpoints greed and an obsession with ownership as the evils of contemporary society. Capitalism is the virus that has infected us all.

Walking the fine line between assertive and brutally honest, Kaloki Nyamai’s passion steers him off the beaten path. Rather than recycling through the traditional gallery roster in Kenya, he winds his own route through Africa and Europe. In February 2020, his artwork featured at two of the largest art fairs in South Africa, the Investec Cape Town Art Fair (Feb 14-16), as part of the group show at the Ebony/Curated booth, and, of course, the Stellenbosch Triennale’s Curator’s Exhibition (Feb 11-Apr 30), where Your Comfort Is My Discomfort, currently stands between installations by the fresh-faced Tracy Thompson and the internationally acclaimed Ibrahim Mahama. Woefully, Mahama could not attend the opening of this incredible celebration of talent from across Africa. Many artists and organisers of the event had difficulties crossing borders.

The reality we live in is one where we are not welcome to roam the planet. The free-spirited cannot explore spontaneously. We need stamps to move and stamps to stand still. We have margins, restrictions, perimeters that have become laws because one person didn’t like another’s face. We are stuck in the degenerative “us vs them” mentality. “A place where we are supposed to co-exist still feels uncomfortable,” says Kaloki Nyamai about his experience in Stellenbosch. “I’m a sociable person,” he adds, “I just want freedom of movement when I go to places, and when I feel different, it hurts.” With this simple, honest statement, Nyamai drives his point home.

As the trustees and curators of the Stellenbosch Triennale 2020 closed their doors to respond to the threat of COVID-19, Kaloki Nyamai considers how a non-discriminating virus can impact our social behavior. Despite our physical distancing, the coronavirus has the potential to bring us much closer, but only once we accept that we are all the same inside; all susceptible, and all looking to belong.

March 26, 2020