Antonello da Messina’s note for Mantegna is in Sebastian’s navel

Antonello da Messina painted Saint Sebastian to ward off the plague. And he hid a mystery in the navel of his athletic body

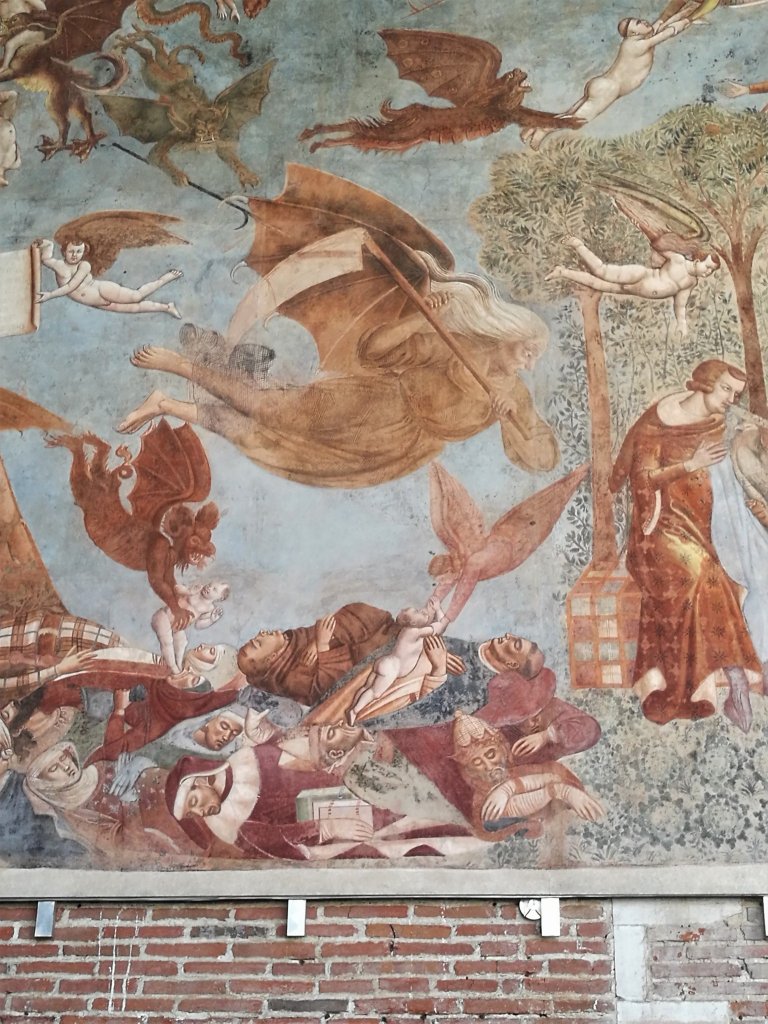

If we were to choose a subject from art history to describe what is happening these days, many apocalyptic visions on frescoed walls, panels and painted canvases scattered around the world would be happily available, for instance, the Triumph of Death painted by Buonamico Buffalmacco in the Cemetery of Pisa between 1338 and 1341 – hinting at his work may be interesting not only for its outstanding expressiveness, but also because the artist is mentioned by Giovanni Boccaccio in his masterpiece, the Decameron, a collection of novellas ideally written during a quarantine.

[Here is what we published about the exceptional restoration of the frescoes of the Cemetery of Pisa, returned in 2018 in their original setting. Ed.]

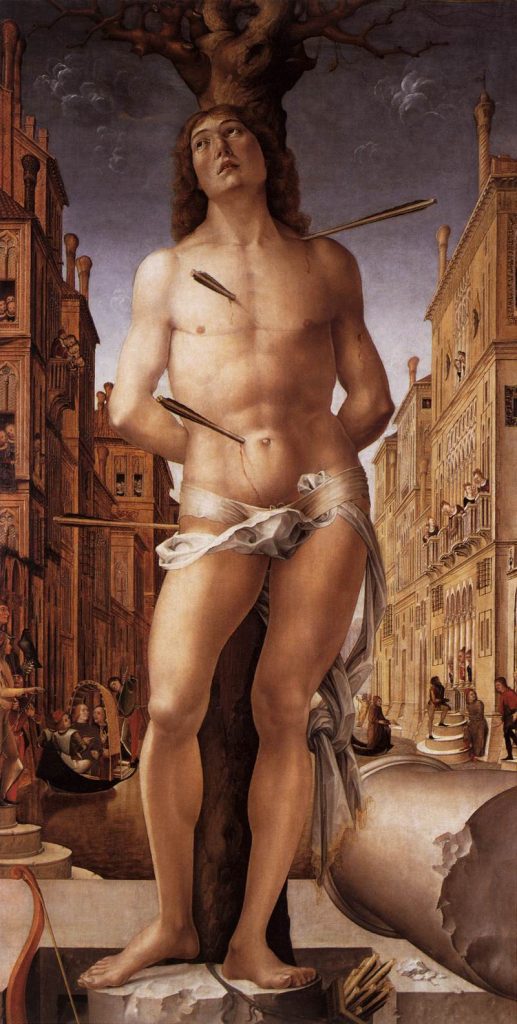

Instead we wanted to choose a positive subject: Saint Sebastian, who is considered the protector against pandemics. For this very topical symbolic value, we decided to dedicate the subject to an in-depth study, focusing on one of the most beautiful paintings ever dedicated to him: the one made by Antonello da Messina in 1478 and now preserved in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden. Our journey begins with a small discovery in this painting, and possibly ends with a coded message.

The navel and the eye

When observing the painting, you can’t help but notice how skillfully it was composed and executed. You can indeed spot its admirable perspective construction, the idea of the human figure acting as a shield for the city in the background, and the arrows that seem to be shot from the observer’s point of view, strongly lowered with respect to the median axis-a restoration carried out between 1999 and 2004 made it possible to identify the exact vanishing point, placed behind the right calf. By simply looking at the painting, however, you may overlook a detail that Daniel Arasse, an art historian who passed away in 2003, noticed.

In one of his essays, he narrates that at some point in his career he had begun to take photographs of the works he saw for real. He said: “[I did so] without necessarily knowing what I was photographing, because you always find what you are looking for. Even when you don’t know what you’re looking for, maybe you’re lucky enough to find something unexpected”. So, after seeing and photographing Dresden’s Saint Sebastian without thinking too much about it, once back home, Daniel Arasse projected the slides of the details onto a white wall, and was surprised to discover that the navel of Saint Sebastian was drawn exactly like an eye: “Not that it resembled an eye, it was an eye”.

But Daniel Arasse also noticed another unusual detail. The navel was placed in a lateral position with respect to the median axis of Saint Sebastian’s body, while obviously it should have occupied a central position. Yet, in the painting, the vertical median axis of the body is well identified and underlined by strong shading. So why put the navel on the side of the axis and not in the centre?

While asking himself this question, Arasse also noted that “if the navel-eye was next to the central axis, on the other side of this axis there was an arrow planted in parallel, which would somehow blind the second eye”.

Why would Antonello put two eyes on the body of his Saint Sebastian, one of them blinded by an arrow? Arasse doesn’t give an answer. He merely recounts that from then on he paid great attention to the navels in the paintings, and that he found other eyes from Crivelli until the Flemish 16th century. But it is one thing to make a navel like an eye, it is another to imagine – as Antonello does – two eyes, one of which is pierced. How do you explain this addition of cruelty on a subject who has already suffered martyrdom?

In an attempt to answer this question it is necessary to go a little deeper into the history of this painting by Antonello, which – to begin with – has not always been considered to be a work by this author.

The birth of the painting and the different attributions

The work was commissioned in 1478 by the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice which was founded that very same year, when the city was hit by a strong plague and lost roughly 15% of its population. The artist painted it over a very short period of time, in the months from the foundation of the School (June) to his death (1449), and up to now this is the most accredited dating among scholars.

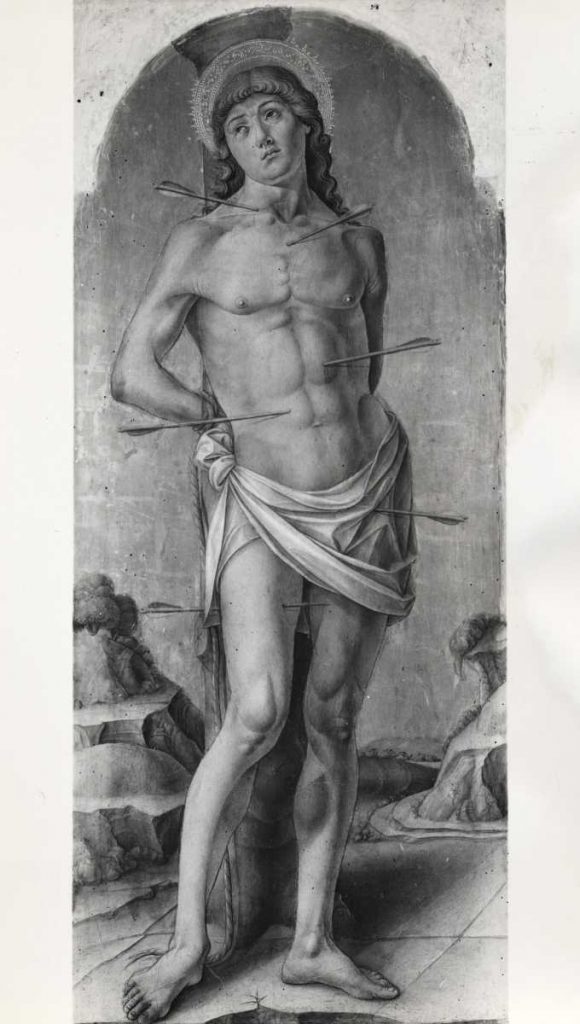

Overlooking the chronology of its ownership, the modern story of this Saint Sebastian begins with the Universal Exhibition in Vienna in 1873, where it was shown as a work by Giovanni Bellini – here the link to our paper about the relationship between Bellini and Mantegna, recently investigated by a seminal exhibition at the National Gallery in London. The attribution was already a source of heated debate at the time. Some assigned it to Francesco Bonsignori, others to Pietro da Messina, some even to Lorenzo Lotto, until Crowe and Cavalcaselle addressed the work to Antonello. It is worth remembering that Giovanni Morelli did not miss the opportunity to mock the attribution to Antonello, except for, years later, making it his own and emphasizing it – here is a link to our paper about Giovanni Morelli.

Today the work is almost unanimously ascribed to Antonello’s catalogue. However, it is still not sure how much this painting actually owes to Andrea Mantegna (now it also should be clear why we have out a link to the Mantegna/Bellini exhibition). And it is here that it might be useful to go back to the navel-eye discovered by Daniel Arasse.

A debt to Mantegna

The Saint Sebastian by Antonello da Messina has been linked to one of the greatest masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance: the decoration of the Ovetari chapel in the church of the Eremitani in Padua by Andrea Mantegna. Specifically, if we look at the scene of the Martyrdom and the transport of the body of St. Christopher frescoed between 1454 and 1457, we notice at least three similarities with the Saint Sebastian by Antonello da Messina . The first one is in the use of perspective conveyed through the forms of the circle and the square. The second can be found in the underlying architecture, which is very similar in the two works. And the third is represented by two analogous figures: the dead soldier, lying in the background on the left, in Antonello da Messina’s work, and the corpse of St. Christopher, equally supine in Mantegna’s fresco.

Put together, these three components are more than mere coincidences; on the contrary, they seem clear and explicit debts of Antonello da Messina to the painter who at that time, in Veneto region, was considered the most avant-garde artist. However, not all art historians are inclined to believe that Antonello da Messina had actually seen the frescoes in Padua in person. It is at this point that one could add to the three clues that ombelic-eye seen by Arasse and also the arrow in the other hypothetical eye.

In the left part of Mantegna’s fresco, in fact, the one with the martyrdom scene, the artist depicts the text of the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Varagine which describes the various tortures the saint undergoes, who – among other cruelties – was tied to a column and shot with arrows, just like Saint Sebastian. In the scene on the left of Mantegna’s fresco we see two arrows, one remains suspended in mid-air near the saint (the passage is illegible today, but can be seen clearly in a copy kept at the Jacquemart-André Museum in Paris), the other instead turns back towards the tyrant who had ordered the killing of the saint, and prodigiously hit his eye; this scene is possibly the most iconic and still the most reproduced image of the Paduan cycle. An arrow in one eye in Antonello da Messina’s work, then, and one in Mantegna’s. At this point there are too many coincidences for them to be merely the result of chance. And the two eyes on Saint Sebastian’s belly could be the explicit declaration of the debt Antonello da Messina owed to Mantegna, a sort of coded message left by the painter in one of his last works.

The symbolic value of iconography

The Saint Sebastian by Antonello da Messina had a great influence on Venetian painting; similar subjects, for the type of posture and part of the setting, can be seen, for instance, in Bartolomeo Vivarini’s (in the polyptych Melzi d’Eril today at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan) and in Liberale da Verona’s (today at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan).

More generally, in fifteenth-century Venice, paintings with this subject were often placed in a central position on the altars, demonstrating just how much epidemics were really feared by the population. But the subject was already recurrent in the fourteenth century (let’s remember the plague of 1348, during which the painters Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti also died) and its popularity did not stop over the centuries. Throughout time, the subject has been given many different shades of meaning, sometimes according to the spirit of the times, sometimes to theological standpoints, sometimes again according to the patrons’ will; however, the meaning of Saint Sebastian has never lost its primary imprint and remains fundamentally linked to the saint to whom the end of the terrible plague of 680 A.D. was attributed. It was in that year, in fact, that the saint was worshiped for the first time in Rome as a protector against the epidemic. As Paul the Deacon recounts in his Historia Langobardorum, when the saint’s relics were brought to St. Peter’s Basilica, the plague ended.

Tunc cuidam per revelationem dictum est, quod pestis ipsa prius non quiesceret, quam in basilica beati Petri quae ad Vincula dicitur sancti Sebastiani martyris altarium poneretur. Factumque est, et delatis ab urbe Roma beati Sebastiani martyris reliquiis, mox ut in iam dicta basilica altarium constitutum est, pestis ipsa quievit.

Paolo Diacono, Libro VI

From a symbolic and iconographic point of view, the power to “return to life” is also intimately connected to a phase of his martyrdom, which however does not coincide with his death. The depiction of Saint Sebastian as a man pierced by arrows may lead us to think that this is how he died. Instead, as Jacopo da Varagine relates, Sebastian did survive that first condemnation ordered by the Emperor Diocletian, and “returned to life”. A few days later he went back again to the emperor to accuse him of persecuting Christians. It was then that Diocletian ordered the soldiers to kill the saint who was clubbed to death.

The reasons for the evil and illness that spread like an arrow through the air can be found in many ancient sources, from Homer to the Bible. And it is because of this symbolic value of the arrow that Saint Sebastian is represented as such in the whole history of art (and not how he actually died). Saint Sebastian stops the arrows of evil with his own body and prevents them from striking others; this is a very strong image, which will interest even twentieth-century authors such as Egon Schiele, at a time when the new plague would take on the face of the Great War, and contemporary artists such as Damien Hirst, in a broader reflection on the mystery of life and death.

April 12, 2022