No leap is ever into the void

A saga of artist jumps through the work of Hsieh, Mureșan, de Dominicis, Perrone, in the wake of Yves Klein’s famous leap into the void.

When it comes to human flight, the first great “influencer” is not Leonardo with his machines, but Rita of Cascia. Back in the 14th century, she spread her arms and flew from her palace to the convent of the Augustinian nuns who did not want to welcome her as their handmaid. After the murder of her husband, a resentful man from the Ghibellini family, the nuns feared retaliation from the opposing Guelfi’s, hence their skepticism toward her admission. Faced with the miracle of her flight though, the convent gave up and so began the new life of the future Rita of Cascia, Saint of the Impossible.

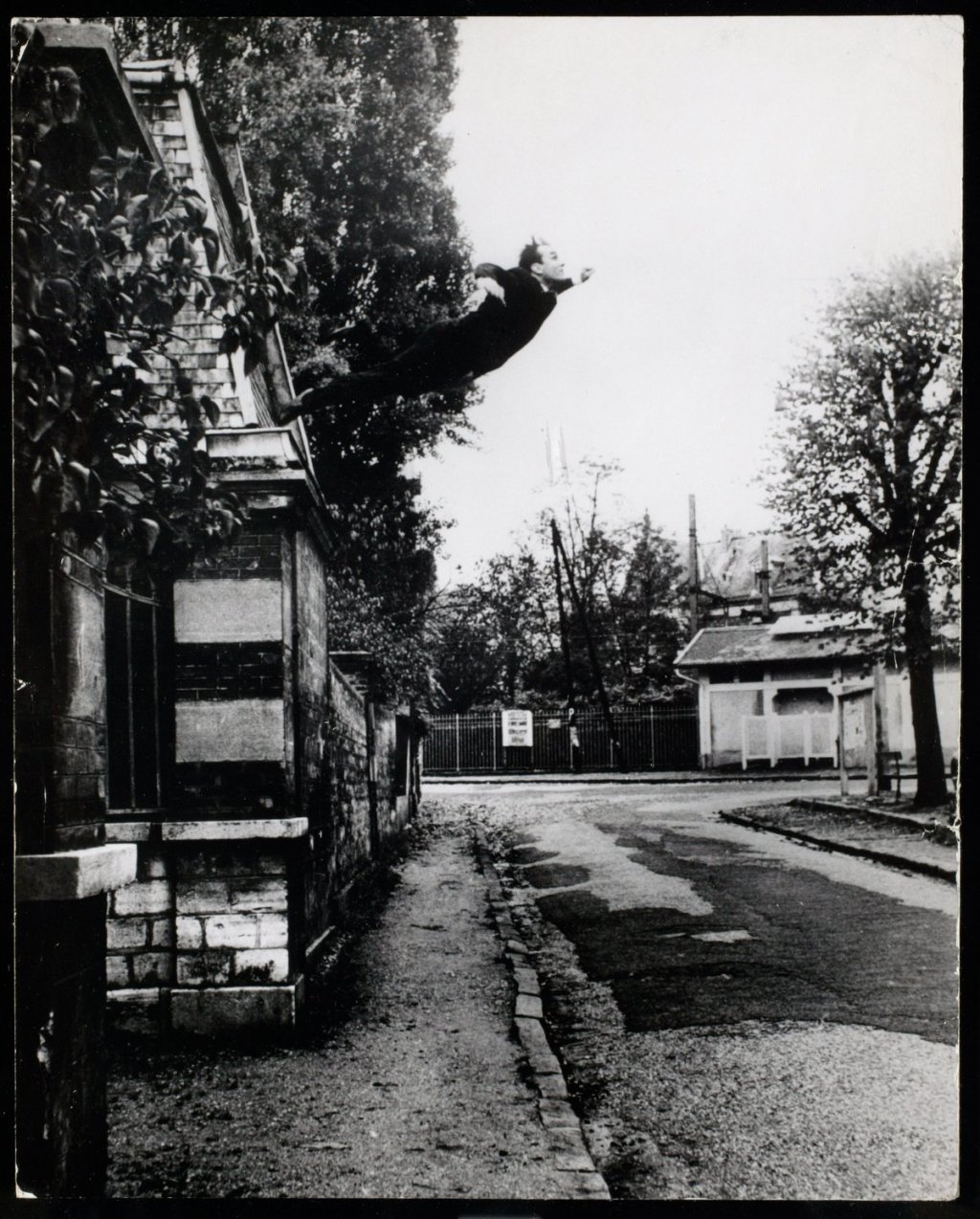

For Yves Klein, great follower of Rita, everything started with this ecstatic flight of the saint. He knew of her cult from his aunt Rosa Raymond Gasperini, as Pierre Restany reports in the biography of the artist. The inventor of the International-Klein-Blue could only be admired by the saint’s night flight. He even imitated it in his famous performance of 1960.

Klein’s Leap into the Void was captured by Harry Shunk and János Kender, two experimental photographers who had also documented the work of Andy Wahrol, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Daniel Spoerri, Niki de Saint Phalle and John Baldessari. Shunk & Kender dropped out of school to find the places where art history was made. Their pictures still capture the chaotic energy, the effervescence and the wit of the performances from the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

As beautiful as an angel, Klein glides with open arms from a roof in the Parisian suburb of Fontenay-aux-Roses. It seems to get up in flight, mystically sucked upwards, like the angels of Giotto in the cobalt blue sky of his Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Not surprisingly, Giotto’s colours are believed to be an influence for Klein’s famous monochrome blu. Ironically, one of the photographs also captures a man on a bicycle, so absorbed in his thoughts that he doesn’t even notice the miraculous take-off.

The leap of faith of the French artist has been compared to the mad religiosity of Jacopone da Todi, who would invoke God by rolling on the ground naked, sprinkled with chicken fat and feathers. So much contrast is there between the absolutely ecstatic leap of Klein and the putrid, biological dissipation of Jacopone, whose divine curses are worth reporting here:

Oh God, please make me sick

Send all kinds of fevers upon me

And toothaches, headaches and stomachaches.

Both the downward and upward directions aim at elevation. The duality of high and low returns in an essay by Yve-Alain Bois where the scholar compares Yves Klein to Piero Manzoni.

Driven by ambition, Manzoni would often bash his rival Yves Klein to relentlessly warn him that there was room for only one of them in this world. It was as if Manzoni had said to Klein: “You want to show gold, I will show shit; you want to inflate the artist’s ego with your monochromes and your immateriality, I will put the artist’s breath in red balloons and I will blow them up.”

With his leap, Klein flew over art towards the immaterial, towards Le Vide or the void, while Manzoni would rehabilitate the formless, brute matter down below. Even though Klein shows us the absence of weight in his performance, he too needed a photographic miracle to achieve the suspension of disbelief in the Leap into the Void. In the performance, the artist was actually gliding onto a sheet held by friends from his Judo practice, although for 50 years people thought that firefighters were holding a tarpaulin to receive him.

The photomontage manages to erase our worries for his health. Without it, we would be thinking of his rescue rather than his dream, that dream of not being there, of disappearing into the void. In 1961 Klein left an ex-voto at the convent of Santa Rita in Umbria: a Plexiglas box with frankincense and myrrh, gold leaf, pink pigment and the famous ultramarine blue; a renewed gift from the Magi, accompanied by a scroll in which he dedicates his practice to the Saint of the Impossible.

[Here is our article about the relationship between Yves Klein and Lucio Fontana. Ed.]

Klein’s Leap into the Void and its followers

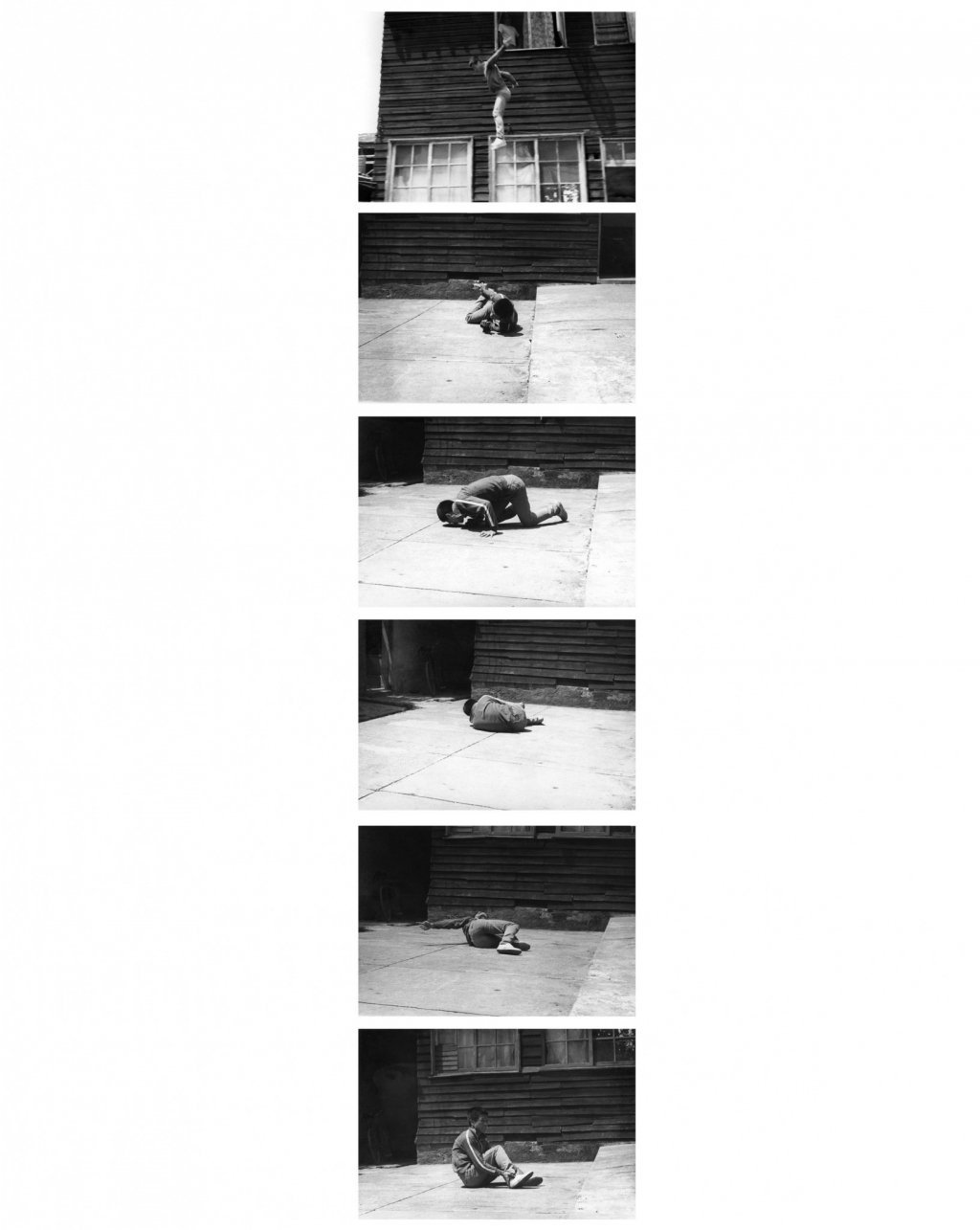

There is a moral dimension in the Taiwanese-born, American artist Tehching Hsieh’s jump from a second floor window in 1973. In an interview with Marina Abramovic in 2017, Hsieh states that his jump piece, the leap into the void, “was more of an experiment than anything else.” He continues: “maybe I thought I was Yves Klein and I could fly like him.”

Hsieh references are also the Gutai group founded in Japan in 1954 and the masochistic jumps in the canvases of Murakami Saburo, which Klein knew well too. Says Hsieh about his jump: “I knew I would hurt myself, but I didn’t think I would break my legs. I overestimated myself … or underestimated the concrete area below.” The camera fixes the whole flight from the window towards the unstoppable splash on the ground. Conclusion: fracture of both ankles. Art and life collapse.

When in the interview Abramovic mentions the unreality of Klein’s flight achieved through photomontage, the performer replies: “You say unreal, but the real jump is very important for those of us who have jumped on a ship, a real leap into the void of the unknown United States seen from the perspective of the clandestine. In a sense, the window is the tragic possibility. It is important that the jump shows a direction.”

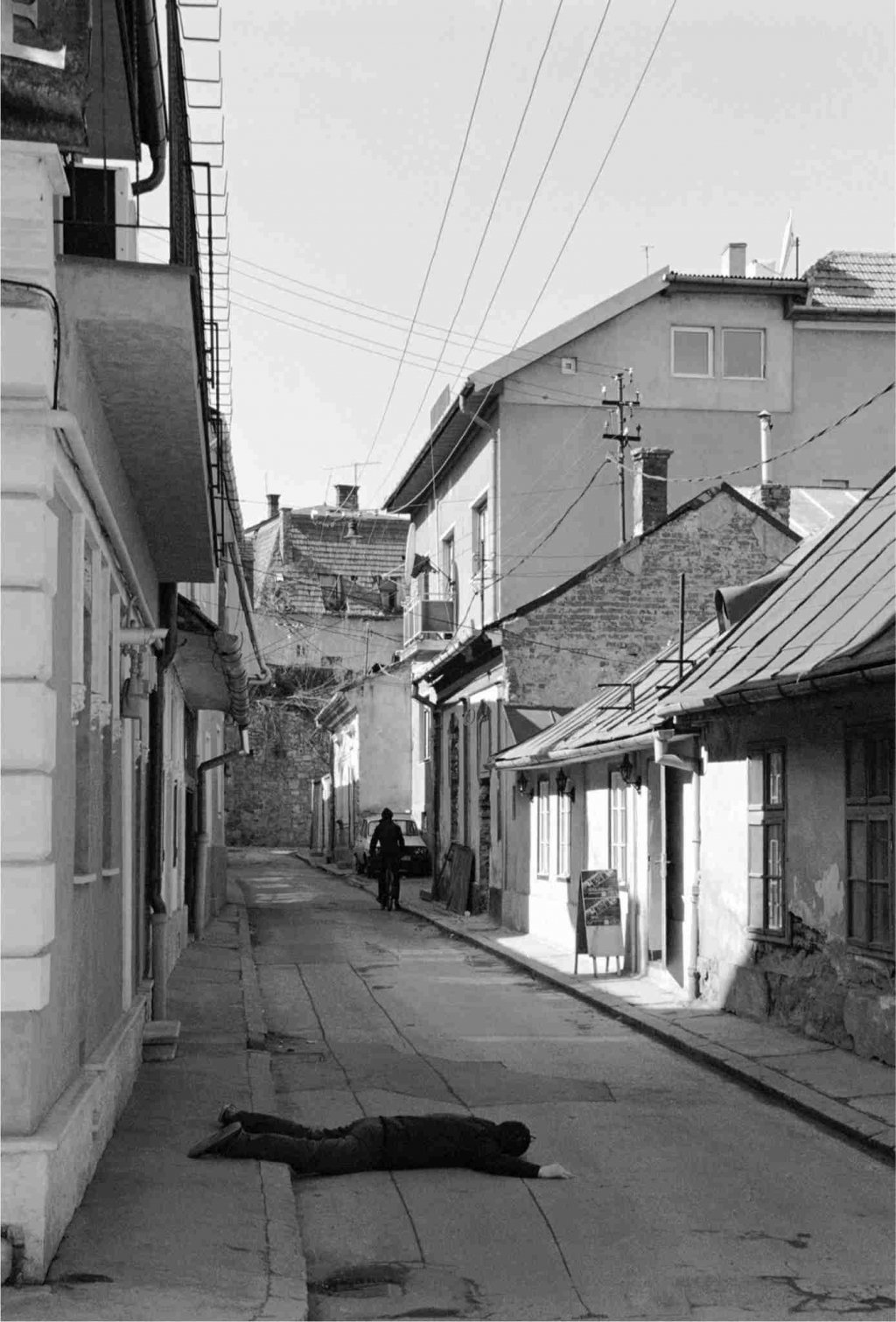

In 2004, Ciprian Mureșan (RO, 1977) made a sequel to the famous Kleinian gesture titled Leap Into the Void – After Three Seconds, shown in the Project Space at the Tate Modern in London in 2012 as part of the Stage and Twist exhibition. The title of the performance hints at what happens three seconds after Klein’s magnificent angel flight. Mureșan’s body, face down on the cobblestones of a narrow street, lies like a deflated tube on the ground, suggesting artistic failure. Forty-four years and “three seconds” after Klein’s flight, hope succumbs under vulgar gravity.

In a 2011 interview with Emily Nathan on Artnet, Mureșan says: “I created a parallel world specific to Romania, which represented the situation of an artist in Cluj in 2004 where nobody cared about art. The difference between my world and the world that Klein represents is embodied in those three seconds, between jumping and falling.”

Klein’s Leap into the Void and Photoshop

The 2010 piece A Requiem: Theater of Creativity/Self-portrait as Yves Klein by Yasumasa Morimura (born 1951) is a photograph of the artist in flight as a self-portrait of Yves Klein. Like Cindy Sherman, Morimura exploits art historical masterpieces as well as mass culture. He appropriates the reproductions of famous paintings, whose appearance is made too familiar by the excessive commercial use, subsisting faces in the pictures with his own, for example Manet’s Olympia and Vermeer’s Woman Reading a Letter. He becomes the face of Frida Khalo and Vincent Van Gogh in some of their famous self-portraits, and with an obsession for details, he impersonates famous actresses too, from the divine Greta Garbo to Marylin Monroe. Double disguised, Morimura goes as far as to play the role of Rose Sélavy, Duchamp’s female alter ego.

A cobweb of subtle ambiguities arises from these images in a progressive shift towards theatricalisation and in an increasingly disturbed imaginary dimension. Despite its precision, the disguise is deforming and self-contradicting. Morimura does not aim at the repetition of the chosen fetish, but at its subversion. Klein’s leap mirrored by Morimura is the death on stage of the famous piece.

An Attempt to Leap

Tentativo di Volo is a 1969 photographic sequence by Gino De Dominicis. The artist, fully dressed in black, opens his arms and shows his chest before awkwardly attempting to fly from the mossy ridge of a mountain. Like a bird, the artist leaps from a height to take advantage of the first glide. Flapping his wings/arms, De Dominicis struggles to take off, jumping all over again with no success. Questioned about this awkward experiment, De Dominicis said he did not know how to swim and therefore wanted to learn how to fly. Repeating the sequence all over again, it is as though the artist wished for the skill to emerge from his DNA, something to be transmitted to his children. In his struggle, the artist projects himself upwards, moves his fingers as if they were feathers, yet nothing happens: the body is too heavy, the mission is impossible.

How can you go beyond what is possible? Can Klein’s aesthetics achieve that? De Dominicis’ Tentativo di Volo turns into a gag that scoffs at Klein’s Leap into the Void and the quest to turn art into the immaterial. There is no heroic rhetoric in these small, goofy jumps. De Dominicis’ work is a caricature of Klein’s famous leap, a winged satirical aphorism full of black humour.

Dangerous Leaps and Holes

Diego Perrone’s I pensatori di buchi is a work from 2002 consisting of 11 photographs of freshly dug holes taken over a period of one year. Says the artist: “You see, everything in this project was born a little by chance, in a Zen way. There are those who walk and there are those who dig.” After having personally dug the holes, the artist-thinker stands naked before the void. The materiality of the earth and the void clash. the artist finally experiences his paradoxical condition.

In 2016, a visitor ended up in the hospital after having jumped into Anish Kapoor’s Descent into Limbo. Fortunately, that pitch black hole was not so deep, but the sense of sucking, of infinite maelstrom was irresistible, given by the absolute black, the Vantablack, patented by the English artist.

This work draws from Kapoor’s meditation on art as metaphysically going beyond itself, just like the defied gravity in Klein’s angelic Leap into the Void. In Jack London’s short story The Shadow and the Flash, two friends face each other in the challenge of invisibility, one using light, the other shadow. Kapoor has chosen to descend into the underworld of blindness, the dark hell of the fallen angel of Lucifer.

Bibliography

- Pierre Restany, Yves Klein: Le monochrome, Hachette, Paris, 1974

- Bois Yve-Alain, Krauss Rosalind, L’informe: istruzioni per l’uso, Milano, ESBMO, 2003

- Harumi Befu and Sylvie Guichard-Anguis, Globalizing Japan: Ethnography of the Japanese Presence in Asia, Europe and America, Routledge, 2003

- AA. VV., Il Piedistallo vuoto. Fantasmi dall’Est Europa, Milano, 2014

- AA. VV., Through the Collector’s Eye. Works of the Generation 2000 from Cluj in Three Romanian Collections, The Office ed, Cluj, Romania 2014

- Gino de Dominicis, Lettera sull’immortalità del corpo, Roma 1970

- Gabriele Guercio (a cura di), Gino De Dominicis. Scritti sull’opera e riflessioni dell’artista, Torino, Allemandi, 2014

- Mircea Eliade, Miti Sogni Misteri, Rusconi. Milano, 1986

November 25, 2020