The quotidian avant-garde of Gustave Van de Woestyne

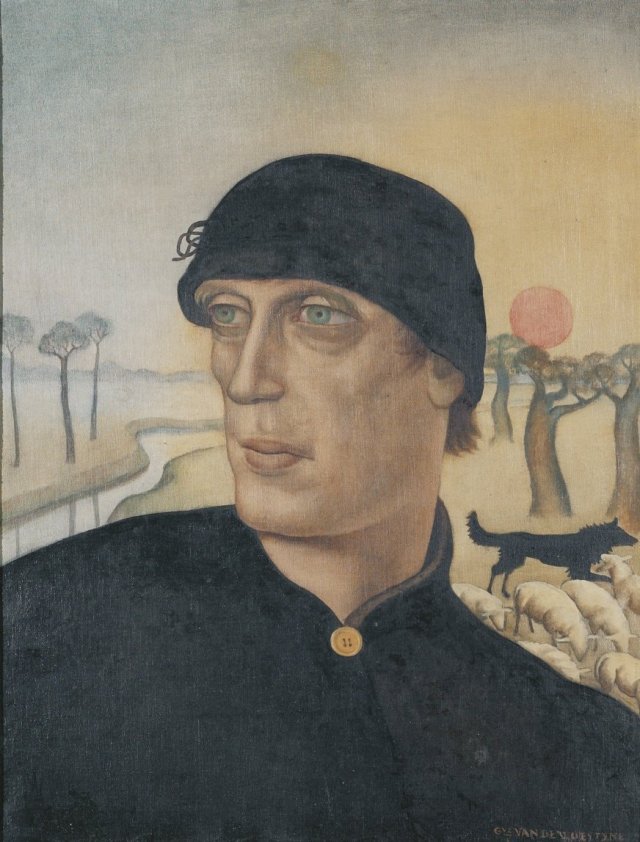

Symbolism and everyday blend in the work of Belgian master Gustave Van de Woestyne, a modernist who was able to make pious and rural life feel contemporary.

The oeuvre of Gustave Van de Woestyne (1881 – 1947) should be situated amidst a climate of generous art production that poured out of Ghent and the surrounding countryside at the beginning of the 20th century. The artists operating at that time became internationally renowned for the way they rhymed avant-garde Western-European tendencies with humble and quotidian scenes from rural life. The group of artists forming the first “School of Latem” – active in the small village of Sint-Martens-Latem – was pivotal in this respect.

Not so much a self-proclaimed entity, but rather a hybrid conglomerate of loosely affiliated artists from the Ghent Academy, they were led by Karel Van de Woestyne (1878 – 1929), the poet who brought French symbolism to Belgium and paired it with a quest for detachment, transcendence and the absolute. The visual artists in this community preferred realism over Impressionism, depicting the simplicity of farmers’ life in symbiosis with nature’s cyclic rhythms. Often referred to as mystical symbolists, artists such as sculptor George Minne and painters Albijn Van den Abeele and Valerius De Saedeleer managed to infuse this seemingly plain subject matter with cryptic and esoteric undertones by capturing nature’s nearly godly infiniteness.

Karel Van de Woestyne’s younger brother, Gustave Van de Woestyne aspired to a career as a painter in this context. Due to the early passing of their father, the two brothers developed an intimate bond in which Karel took on a care-taking role, which persisted throughout their entire lives. The life of Gustave Van de Woestyne is easily traceable through the many accounts he wrote himself, most notably his memoirs, which emphasize the relationship with his brother, proclaimed to be his best critic.

[For another special relationship between an artist and his brother, this is our translation of an important letter Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo. Ed.]

Just like Karel, Gustave would also organise his life and art around thorough philosophical reflections. Even at a young age, he was very much concerned with existentialist questions, which quickly became amplified with religion. The artist made several attempts to run a clerical life in various cloisters, but was too driven by a creative desire to solely devote his existence to the church. He decided to appropriate his painterly palette as the tool through which he would spread the word of God, and deployed subtle earthly colours to portray Catholic values such as simplicity and humility, love for God and respect for all species, human suffering and hope. He recognised the act of God in each human gesture, in each natural manifestation – a sincere admiration that radiates through his entire oeuvre.

The artist embodied this spiritual dedication with an open stance on the world. His eclectic body of work is informed by his receptiveness for the developments of Modernism. Various trips to Paris confronted him with the nuances of avant-garde artistic novelties apparent in the work of Rousseau, Picasso and Modigliani amongst others. He incorporated these stylistic developments in his own practice, alongside references to the Flemish Primitives and Brueghel, generating an unconventional allegorical aesthetic that wasn’t easy to digest but did make him stand out.

Gustave Van de Woestyne’s oeuvre is often categorised according to distinct recurring motives, described by his brother as the ‘moral groups’: farmer portraits, religious scenes and deeply personal inner experiences – a tripartite that was heavily influenced by his short time with the Cistercian order. He visualised the austere life of peasants with great dignity, honoring their sense of responsibility through characteristic portraits of skewed faces experiencing the hardships of life. While these evocations hint at the universal and everlasting work of the godly creator, his explicitly religious scenes convey his own personal suffering. Christ and Maria became protagonists in his expression of sorrow, which resulted in a body of work that was heavily critiqued as being blasphemous, although Van de Woestyne himself continued to defend these works as his best.

In the mid 1920s, after two decades of heavy-hearted imagery and subject matter, Gustave Van de Woestyne found comfort in portraying his wife Prudence De Schepper. Their intimate trajectory took shape as a nearly sacred voyage: ranging from emphatic observations on the moods of his spouse, to touching portrayals of wife and child. Overall, Van de Woestyne’s introspection and self-analysis runs through his entire body of work, much like the artist observing and commenting on his own place in the world. The endless production of self-portraits stand testimony hereof.

Gustave Van de Woestyne was a dedicated artist, working steadily on his career and network of benefactors and fellow artists. During the First World War, he was based with his family in Great Britain, where he became acquainted with businessman and art collector Jacob de Graaff, who would continue to support him as well as other artists from the Latem group. On his return, he had already gained a solid position in the Belgian art scene. It’s in 1913 that the Brussels-based art patrons David and Alice van Buuren purchased their first work by Van de Woestyne, marking the beginning of a longstanding relationship which they maintained with many artists. Their house in Ukkel (now a private museum) is filled to the brim with artworks by James Ensor, Henri Fantin-Latour, Paul Signac, Jean Brusselmans and Frits Van den Berghe. Between 1928 and 1931, they commissioned Gustave Van de Woestyne to create seven still lifes for their dining room; perfectly encapsulated within the modernist Amsterdam-styled architecture of the house. The pair acquired a substantial collection of works by Van de Woestyne (32 in total), which made them crucial in the conservation of his oeuvre.

When his brother and mentor passed away in 1929, the artist took over the directorship of the Academy of Fine Arts in Mechelen from him, and also taught in Antwerp and Brussels. Even though these prestigious positions confirmed his stature as an artist, he also experienced them to be limiting for his own creativity. He would continue to paint up until his death, though less relentlessly than before. His palette became more neutral and humble. Serene Christian scenes again took front-stage, expressing the diminishing energy of his elderly years.

[An important exhibition of works by Gustave Van de Woestyne is currently on at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent. Ed.]

November 25, 2020