Joseph Yoakum and adventurous facts

Joseph Yoakum has us going between the mundane quality of things in front of us and the extra-ordinary quality of their reasons in the world

It is in trying to trace back Joseph Yoakum’s life that a significant clue to understand his work begins to appear. From miswritten birth certificates and self-fictions, to unclear genealogy or locations, the investigation around his character soon requires a lot of surrendering. It seems now that a lot of biographical errors were published. Much of what he told about his life was said to be invented. But despite his romanticized life-stories, much of it is grounded in facts.

[A retrospective exhibition of Joseph Yoakum is currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago. Ed.]

What we can gather is that Joseph Elmer Yoakum was born in Missouri in 1890 to a former slave (French-American, Cherokee and African-American descent) and a Native American, in a family of ten children. Yoakum says to have been born in 1888 near the village of Window Rock, Arizona. No record was found of him being born in that area. Worked in railroad circuses, as a horse-handler, billposter, miner, janitor, carpenter, served in France in WWI, married twice, travelled four continents… but unclear or exaggerated testimonies of the many lives of Joseph Yoakum still leave us a blurred-out map of who he was. Yet these stories don’t seem to contradict each other. They merge or overlap in a long adventure. We are never entirely mislead. Same as for his life story, we have to accept to dive into his vaporous drawings with a trust that won’t ask for explanations. He mostly began to draw at the age of 72 in Chicago, and within those ten years before he passed away, he produced around 2000 drawings.

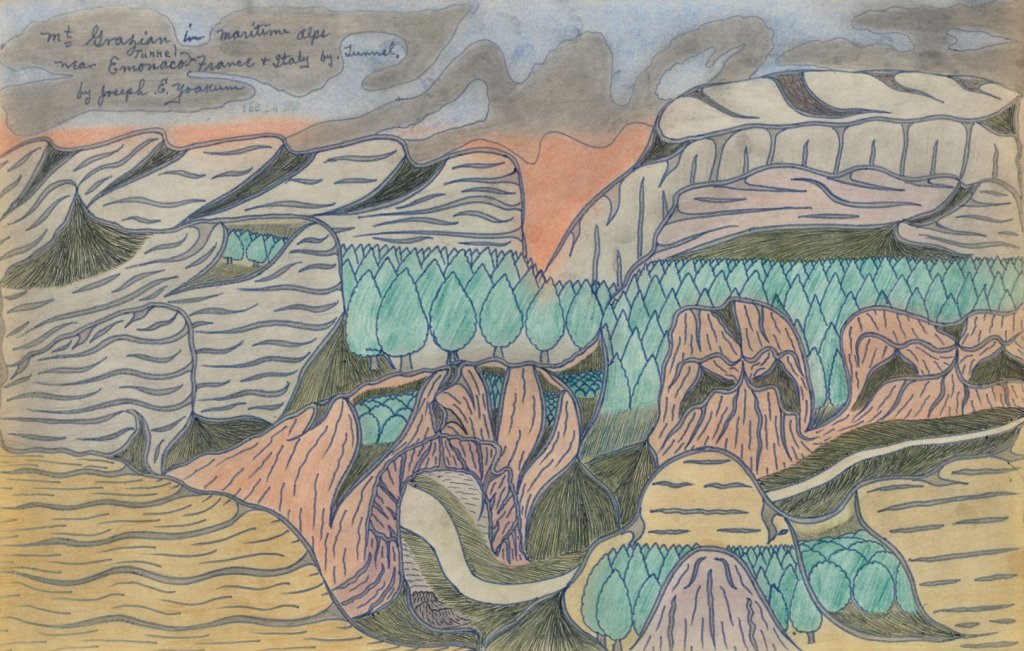

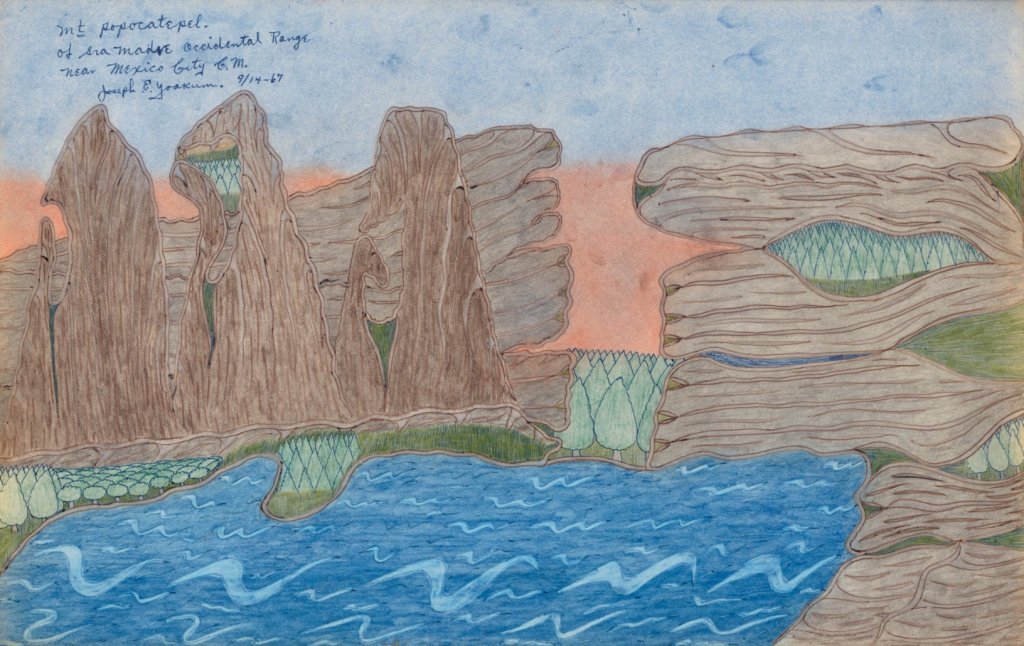

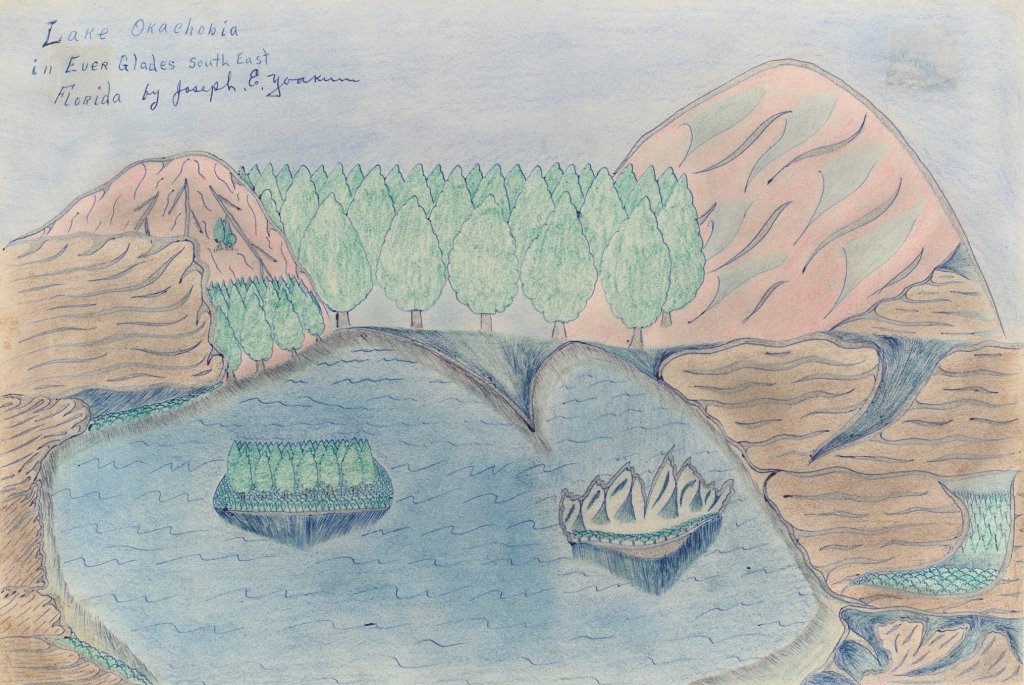

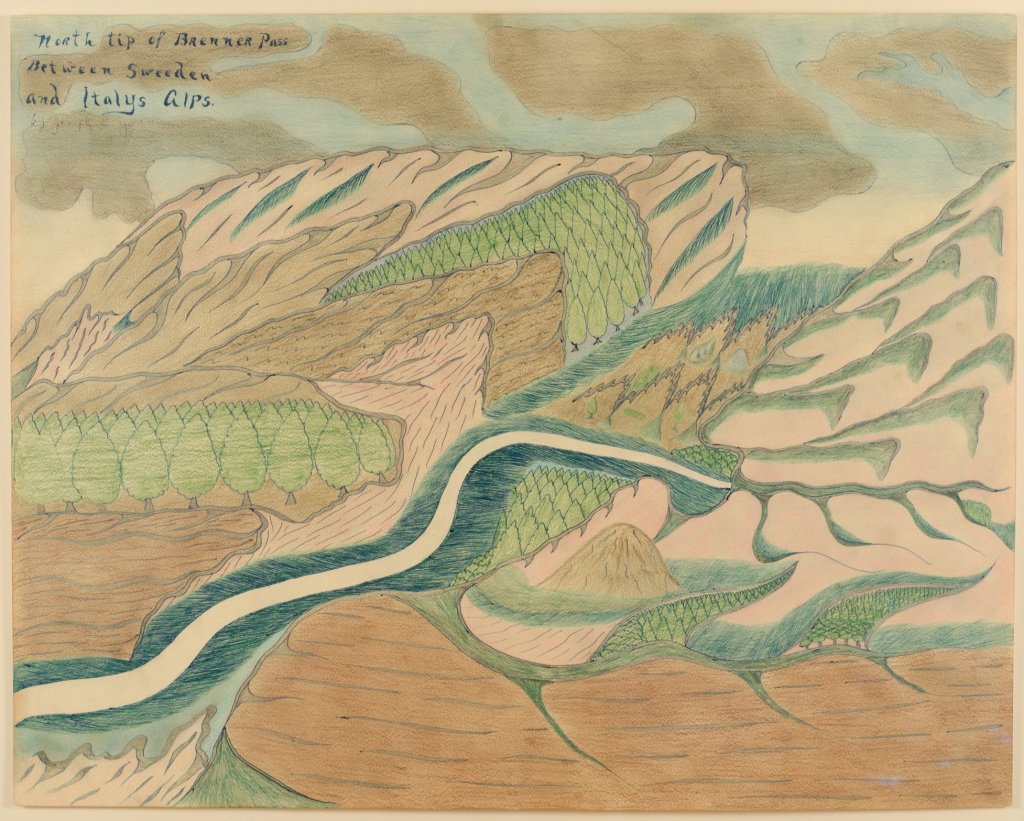

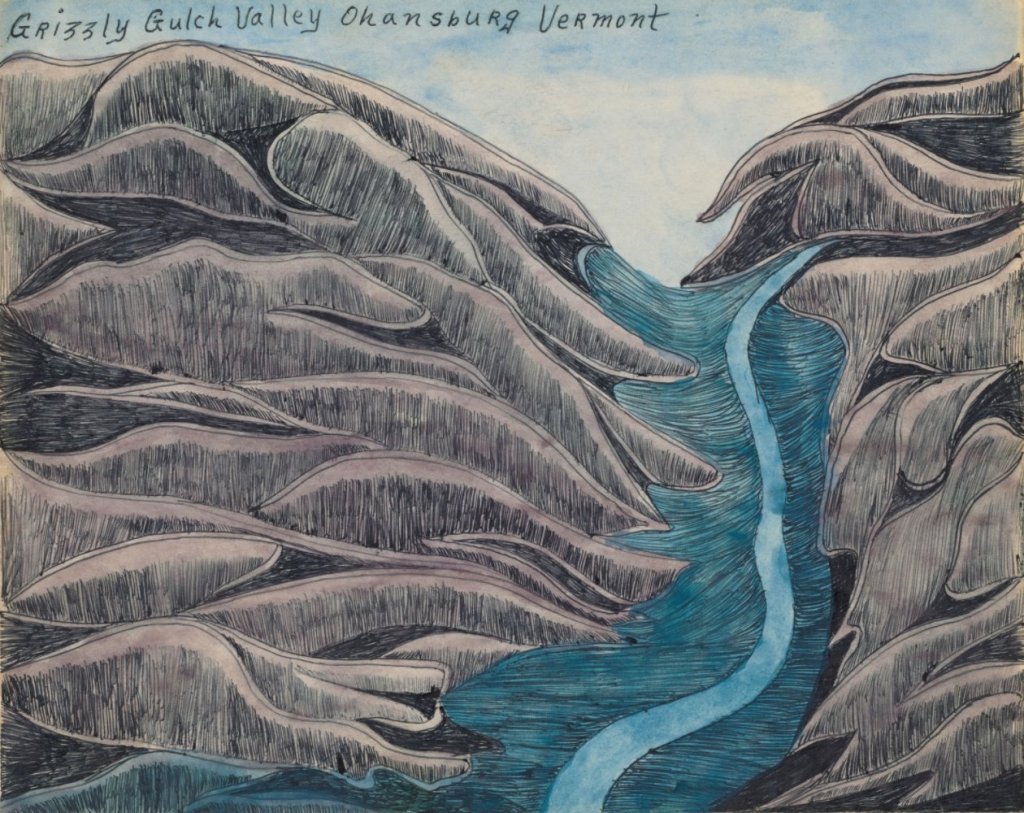

The perspective in them is mostly flattened but natural elements are fluid and vibrating. Rocks, trees or clearings are as if bending under some kind of strong wind. If there is a feeling of depth in some drawings, it is often contradicted by flat backgrounds. The representation of topography is schematically aestheticized, reminding of 16th century Persian paintings as much as pre-Columbian art.

What one could brutally summarize as childish is a seek for clear and simplified depiction of a context. If a place was populated by cows, or full of trees, this imagery will be taken from contemporary sources, creating signs that will be serially repeated throughout the drawing. Yoakum’s work seems to be about recognizing and understanding. His pictures are images as an atlas would have, and at the same time they are filled with vague sensations.

Joseph Yoakum was essentially a loner. There is a simultaneous sense of belonging and not belonging in the views offered by his landscapes. The sense of belonging is a transcending one, a recognition of lands, a becoming together within floating territories. The not-belonging sadly seems more daily. It carries the everyday reality of being an African and Native American in the United States in the 1950s, with the generalized lack of access to the most simple things this implied. Yet his drawings feel like they are diluted and fuelled by many experiences in many other “places where life was much easier for blacks” as he said.

[For more about racism and the 1950s American art world, here is the story of Horace Pippin. Ed.]

I had it in my mind that I wanted to go different places at different times. Wherever my mind led me, I would go. I’ve been all over this world four times.

– Joseph Yoakum

Hazy landscapes, segmented maps and disappearing recollection: Yoakum’s colorful drawings are memories from his travels. His works seem to be the ones of a wistful bird. Seen from a distance, passing through, from higher up. Remembered, made-up or mistaken. Despite precise cartographic captions written on every drawing, they look closer to a bright day-dreaming. In parallel, there is a dedication and very soft precision in depicting places “as they are.” But from where?

Because of its place in our psychic life, a remembered adventure tends to take on the quality of a dream. Everyone knows how quickly we forget dreams because they, too, are placed outside the meaningful context of life-as-a-whole. What we designate as “dreamlike” is nothing but a memory which is bound to the unified, consistent life-process by fewer threads than are ordinary experiences. We might say that we localize our inability to assimilate to this process something experienced by imagining a dream in which it took place. The more “adventurous” an adventure, that is, the more fully it realizes its idea, the more “dreamlike” it becomes in our memory.

– Georg Simmel, extract from The Adventurer, 1911.

There is a lonely feeling in Joseph Yoakum’s works, as if coming up with something that’s missing, or was never there, but is needed. It is puzzling to witness something that simultaneously offers distracted impressions and the regularity of facts. His depiction of land hovers between experience and transcendance, moving beyond times and places.

Joseph Yoakum was a Christian. His faith was central to his work and he said his drawings were “a spiritual unfoldment.” He speaks of “spiritual remembrance” where the subject is finally revealed to him after the drawing is done. This belief implies an interesting temporality that, as his drawings, doesn’t really bother with linearity. The reasons for such revelations equally pre-exist, formalize, and live on after the works, in an undifferentiated way.

…the work of art exists entirely beyond life as a reality; the adventure, entirely beyond life as an uninterrupted course which intelligibly connects every element with its neighbors. It is because the work of art and the adventure stand over against life (even though in very different senses of the phrase) that both are analogous to the totality of life itself, even as this totality presents itself in the brief summary and crowdedness of a dream experience.

– Georg Simmel, extract from The Adventurer, 1911.

Revelations, “dreamlike” memories, total maps and fragmented histories. Forget about double-checking. It’s a journey to go over the ordinary and beyond it. A travel through dubious realities and adventurous facts. You believe what you see as much as you see what you believe. Joseph Yoakum has us going back and forth between the mundane quality of things appearing in front of us, and the extra-ordinary quality of their reasons in the world and in us.

Bibliography

- Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum, By Derrel B. DePasse, 2000, University Press of Mississippi.

- The Adventurer, Georg Simmel “Das Abenteuer,” Philosophische Kultur. Gesammelte Essays ([1911] 2nd ed.; Leipzig: Alfred Kroner, 1919). Translated by David Kettler.

July 26, 2021