Niklas Taleb: staging privacy with no cunning

Somehow staged and performed, yet down-to-reality, the art of Niklas Taleb presents his private sphere without an annoying sense of cunning

To meet Niklas Taleb (b. 1986, living and working in Essen) is to be confronted with a degree of humbleness greater than what most encounters provide. His life experiences are the foundation of his art to such an extent that one might wonder about egocentrism, a term that, however, can’t be applied to his persona. His artwork lives in a fruitful space between unpretentiousness and the desire to share one’s private sphere with the rest of the world. For those who never met him, the impression stays insofar as Taleb’s work is skilfully able to convey unpretentiousness through otherwise deeply self-centered art. This might be possible for different reasons: for a change, the struggles and pleasures of common life in a medium-size German town, a life consisting of parenthood, supplementary work, friendships, habits, etc. are for once told in first person with honesty and subtlety; or his sensitivity allows him to dig into his life until universal concerns are reached; or he just strikes with his ability to avoid the promotional tone we too often feel with people sharing their own business with strangers. Ultimately though, what matters in Taleb’s art is its way to be staged without being cunning, a way he is able to follow by mastering the balance between form and subject, image and object, [1] interiority and exteriority.

Building Subtly

A trained photographer, Taleb rose to prominence with a solo exhibition titled Dream again of better Generationenvertrag at Galerie Lucas Hirsch in Dusseldorf, whose atmosphere of domesticity resonated with many in the early pandemic-related lockdowns of 2020. His photographs presented moments of daily life in his house: his daughter eating, a carrier bag hanging on the wall, a corridor. To that, Taleb added a shot of one of his close friends in a Vietnamese pagoda in Germany, where, we learn, the man was posing for Taleb’s girlfriend, the artist Phung-Tien Phan–together with the other pieces in the show, the presence of this work reflected on the extended boundaries of family.

Some reviews of the exhibition focused on the intimacy of the photographs, perhaps leaving out to what extent that intimacy was manipulated through the specific ways of presentation: the handmade wooden frames; small interventions to the gallery architecture; the peculiar glass-pane display; specific image compositions; the unfolding of the narrative through the series of works. These things came across as accessories to what might have been a show of photographs depicting personal matters, but were instead primarily responsible for Taleb’s aesthetic more than any alleged subject. [2] Forms mingled with substances in this exhibition, as ultimately Taleb’s work walked a tightrope hanging over the fields of staged photos and snaps: his pictures could be described as informal, were they not so smartly built-up (materially and compositionally); or to use the Jeff Wall categories of photographers, Taleb could be said to be a “hunter and farmer” simultaneously. [3]

Experiential Truth

Despite its popularity, memoir as an artform has granted little philosophical investigation. However, this literary genre, as well as its declinations in visual art, prompts many complex questions. Taleb’s work hints at some of them, although it is not memoir in the strict sense of the word–it is not so much about his own self than what surrounds him, what crosses his paths in the world. Moreover, the old-fashioned autobiographical talk of the big personality as an agent of his destiny and his self-indulgent pleasure in writing his own book is nowhere to be found in Taleb’s work.

Instead, his art seems to argue for a loose position in the debates over truth in autobiographical art. In respect to literary memoirs, Helena de Bres mentions the difference between factual truth and emotional truth, [4] where the former is the correspondence of artistic statements with facts, and the latter is what stays loyal to the work of art. It is the otherwise called “experiential truth” [5] of the artist who can help us see what it’s like to live what they live. We ultimately don’t care about Taleb’s actual private life as we do about his own experience and presentation of it. To quote Carlos Lynes, Jr’s thoughts on Proust–perhaps the author who best gave us a constructively artistic account of his own life experiences: “[We should] explore [Proust’s] great novel as a poetic creation, a unique vision of the world objectified in an autonomous, self-consistent aesthetic whole, rather than a thinly-disguised autobiographical reminiscences. […] In reading a novel or a poem as such, one is not interested primarily in the author or the genesis of the work or in its literal correspondence with actuality, but one does expect to find the novel or the poem itself directly significant.” [6]

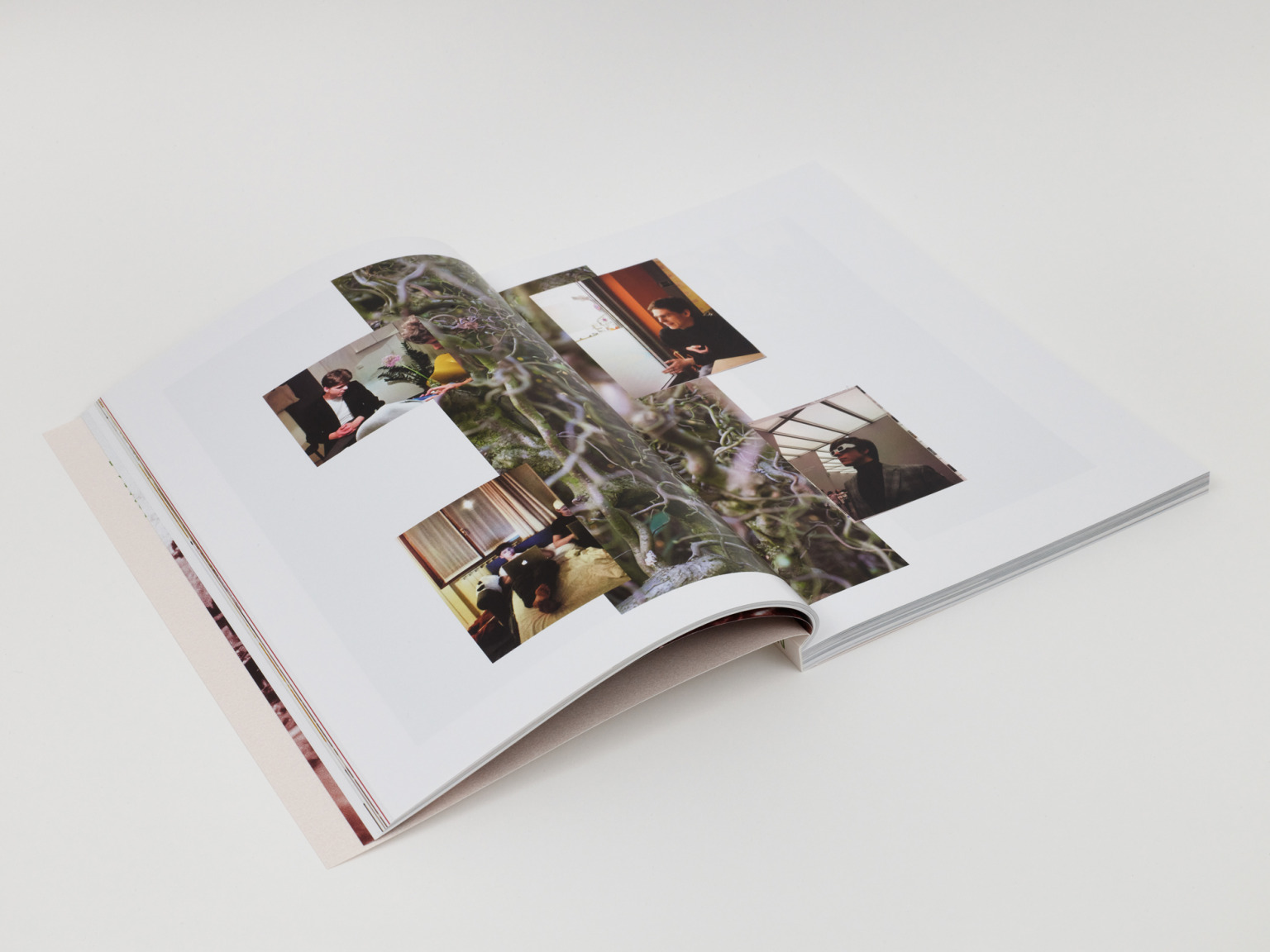

For his recent contribution to the last Le Chauffage magazine (2022), the artist took the topic of the issue–the photo-essay form–to again present himself with honesty. This time Taleb focuses on his friendships, assembling a sequence of old and recent photographs he took of a close friend, who had just moved away from his home town of Essen. During a recent studio visit, he mentioned to us how the departure of a long-time, intimate friend felt like the death of one of those famous people we deeply respect. The title Operation: Doomsday (1999), also the title of an album by the late rapper MF Doom, hints at the loss of those dear to us, at the same time sounding slightly sarcastic in its apocalyptic tone. The game between proximity and distance, whether literal or metaphorical, is played with mastery. Taleb put together his magazine contribution by juxtaposing images of his friend with those of plants from a nearby park. The curly and tangled branches, perhaps an allegory for crossing paths, serve as a staccato in the narrative of the sequence. By exploiting the expectations of the magazine readers, who are promised a photo-essay albeit experimental, Taleb again seems to stage the subject, recounting moments of a friendship throughout the years with unassuming ingenuity. What emerges is the experiential truth, that is, things that are true to the experience of those who share them with us through art.

Blurred Center

Friendship, mixed with the specific context of the artist’s supplementary job, was also the topic of Taleb’s recent exhibition at the Bonner Kunstverein titled Live in Paris (2021-22). In almost all of the photos on show, the subject is his closest colleague at the job where Taleb moonlights–a person, he told us, he respects for her highest moral integrity. The apparent unselfconsciousness of Taleb’s pictures, who only at first sight seems to steer clear of strategy and staging, is present again in this exhibition with his typical solutions seen in previous works: the material side of the photographs, with the use of handmade, specific frames, whose mode of presentation is never seeking neutrality, as well as the seemingly casual and supposedly snappy compositions. What is especially interesting in respect to the argument about memoirs and humble self-centredness in this show are a couple of pieces where the artist seems to offer nothing more than his bare view from his desk. For example, in Reading ( ) the lines, the camera pointed to an empty glass of water suggests the atmosphere of what would likely be a dull office environment were it not for an inspiring colleague. The work titled It can be done but only I can do it presents her, photographed from the same desk, solving the problem of not looking over-staged by presenting the picture in a tiny format printed on a discarded piece of paper.

The same piece is also included in Taleb’s recent exhibition at 15 Orient in New York titled s Place (2022), which features newer and older works. Among them are a few showing childhood in different forms. We know by now that the child in question is the artist’s daughter, whose shadow appears in two pictures (Main Character Syndrome (1) and Main Character Syndrome (2)) in what, we suspect, is the family’s Essen apartment. The child is also present in Für Opa with one of her drawings, which Taleb places on top of a computer keyboard, suggesting the common struggle of juggling careers with raising a child. Less commonly, this artwork seems to put forward the debate on intergenerational justice, where duties to the young, or even to the unborn, are sometimes seen as incompatible with duties to current adults, and surely with our own selves. [7]

Other works in the show at 15 Orient seem to confirm that Taleb is after those simple things that, as Charlotte Cotton puts it, are “imaginative triggers of great import.” [8] Shadows, children’s drawings, computer keyboards: those are tools for an expert semiotician, who again seems happily torn between nonchalant snapping and precise construction, all in the name of sharing his own personal space. The work titled Boy at risk II adds poker games to this metaphorical toolbox of “simple things”, as it depicts a view of Taleb’s desk where a second screen shows people playing at poker tournaments. As a kind of visual background music, the artist confirmed to us that the presence of concentrated faces on a seldom-watched screen helps him concentrate too. Many artists have strange habits while they work at the studio. For example, Allison Katz says she likes to listen to–just listen, not watch– tennis and football matches while painting. However, not many artists use these personal facts in their art, as Taleb does in his picture Boy at risk II. Apart from their subjects, this and newer works in the show, with their attention to presentation through his signature self-built systems–again Taleb’s self seems unavoidable even on a material level–confirm his artistic concerns.

For some hardcore old-fashioned photographers, Taleb’s work might be a persiflage of the medium: he might shuffle some of its classical categories– mostly that of staged and snapped–a bit too relaxedly; his interest in the materiality of presentation might seem out of place in a medium that, for some, is a matter of image-making. However, if those thinkers are likely to believe that photography is about uttering reality through the lens, eye, hand and life of the author, Taleb’s work is no humiliation of photography but an honest elevation.

[1] About the difference between images and objects, says Lucy Soutter in what she calls “contemporary art photography: “An image is an infinitely reproducible visual form that can be enlarged or reduced, translated from one form to another, retaining its recognizable identity. Whether viewed on a page, wall, screen or other surface, a photograph is never just an image – it always takes specific material form. Our drive to read the subject matter of images frequently displaces our awareness of their properties as objects.” In the case of Taleb’s work, the material properties of photographs are accentuated not to take away attention from the subject but to complement it in the balance he seeks. Quote above from Lucy Soutter, “Why Art Photography”, Routledge, 2013, p. 112-13

[2] In respect to the departure from meaning and its comeback in form, it is interesting to quote photographer Lynne Cohen on the construction of her own frames for her pictures: “I think the resulting pieces are more complete as objects and the border between the picture and the world no longer so abrupt.” From the catalog of “No Man’s Land: The Photography of Lynne Cohen,” National Gallery of Canada, 2001.

[3] “The hunter is said to be the photographer who tracks down and captures images, the farmer is the one who cultivates them over time.” Jeff Wall paraphrased in Charlotte Cotton. 2014. “The Photograph as Contemporary Art.” Third edition. New York, New York: Thames & Hudson.

[4] Helena De Bres, “Artful Truths” – The Philosophy of Memoir. University Chicago Press, 2021, p.4.

[5] Ibid. p. 65.

[6] Carlos Lynes, Jr., “Proust and Albertine: On the Limits of Autobiography and of Psychological Truth in the Novel.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Vol. 10, No. 4.

[7] Philosopher Derek Parfit in Reasons and Persons puts the question in terms of rationality, arguing that it is reasonable and not merely intuitive to care about others, including future others, instead of ourselves. For more about Parfit and art, here is our homage to the late philosopher.

[8] Charlotte Cotton. 2014. “The Photograph as Contemporary Art.” Third edition. New York, New York: Thames & Hudson, p. 9.

November 10, 2022