The best six art fabricators

Here is a list of the world’s best art fabricators, showing that behind the most ambitious works there is often an exceptional technique

A couple of years ago from the columns of the New York Times, Nancy Hass asked one of those questions only mass media can ask: aren’t art fabricators the most important people in the art world? After all, gone is the time of the manually skilled artist. Today it is all about executing a vision and art fabricators are the necessary condition to achieve just that. There is of course a lot of truth in this statement, but things do get a bit more tortuous. Deskilling is no longer a fad and many artists take their own manual labor very seriously these days, no matter their age or the scale of their art.

[Here and here for more about emerging artists’ love for traditional techniques. Ed.]

The following selection of top art fabricators brings us right in the middle of this debate. From the large to the small, spanning materials, focuses and expertise, we made our choice of the builders of artworks in an age where artists like to play that role again. Our selection is neither conclusive nor does it aim at confirming specific views of the art world today though. Our picking was (hopefully) no cherry-picking. Yet the list offers a few insights into the world of art fabricators today and their role in the never-ending art vs craft conversation.

UAP

UAP is perhaps the largest and most international art fabricator on this list. It was founded in 1993 in Australia by brothers Daniel and Matthew Tobin, who both attended a fine art school specialised in painting in the late 1980s. Daniel Tobin told us how, more than the school, he enjoyed spending time at a foundry nearby where he and his brother learned casting and the other skills in the field. After his studies, the two brothers set up their own foundry in Brisbane, initially producing for Judy Watson who was making her first public art for the city of Sydney. About his job as an art fabricator, Daniel Tobin told us: “Although my brother still makes artworks quietly on the side, I figured out pretty early that I would be better off assisting other artists and making their own work instead of mine.”

UAP is now an international reality. By securing large commissions for the International Expo Shanghai in 2010, they were able to establish their presence in Asia. They now operate in Shenzhen and Singapore too, with a design office and fabrication facilities. UAP also recently acquired the New York-based Polich Tallix art foundry, a historical fabricator operating since the 1960s and responsible for the making of works by heavyweights such as Roy Lichtenstein, Helen Frankenthaler, Frank Stella, and more recently Jeff Koons and Louise Bourgeois. Says Daniel Tobin about the acquisition: “Dick Polich had no plan on how to continue his legacy after his retirement. We stepped in and he was comfortable with us taking over. Now I feel we are the custodians of his incredible know-how.” Even at the large scale such as UAP, where the range of services broadens to include logistics, architecture and even legal consultancy, art fabricators still deal with the very human challenge of working with those who “need to put their own soul in what they do” as Daniel Tobin describes artists.

Cirva

If UAP Company is the largest art fabricator on our list, Cirva might be the smallest. This glass workshop located in Marseille in France focuses on emerging artists and research into glass making. Contrary to all the other fabricators mentioned here, Cirva is mostly a publicly funded institution. It was started by the French government in the early 1980s as a response to the studio glass movement in the US and to promote glass making in art and education. Cirva was first created within the art school of Aix-en-Provence near existing glass industries but later moved to the nearby Marseille to take advantage of available industrial spaces within an urban context.

Cirva does produce glass sculptures for artists on commission sometimes, but it mostly offers facilities for research and experimentation with glass at their premises. As Cirva director Stanislas Colodiet told us: “The idea behind Cirva is to see what happens when an artist who doesn’t know much about glass making meets a technician who knows all about it but needs to go beyond this preconceived knowledge. This encounter can sometimes lead to no production at all, but it can also lead to great discoveries.” Among the most fruitful collaborations between artists and Cirva, Colodiet mentions Gaetano Pesce in the 1990s and more recently the work of emerging artists Veronika Sedlmair and Brynjar Sigurðarson. Asked about the biggest challenge faced by the institution right now, Colodiet brings up that of building a permanent and public place for the collection and archive of Cirva. Artists who spend their time researching there often leave an artwork as a gesture of gratitude. This collection is not yet as visible as it should be according to the director. Perhaps a new museum is in the making.

Henraux

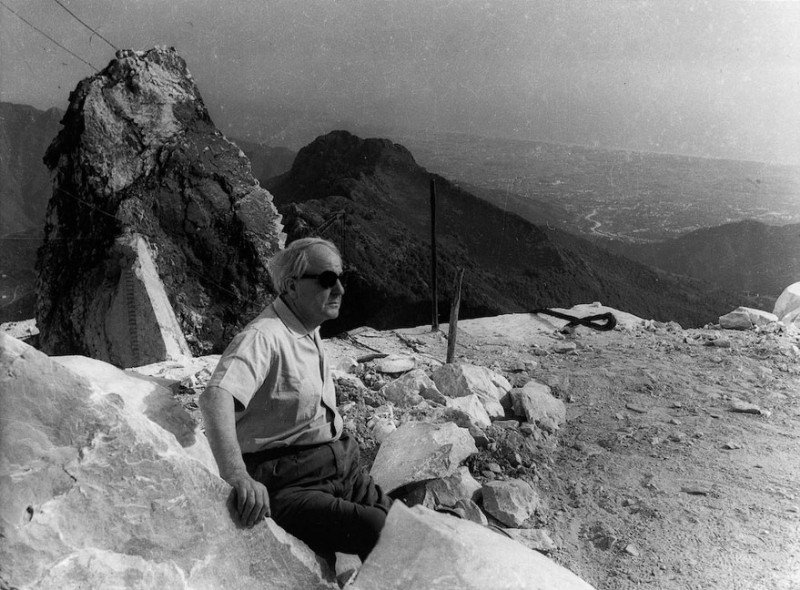

The tradition of white marble for sculptures goes back to the beginning of art. The quarries in the region of Alpi Apuane, which includes Versilia and Carrara might be a bit more recent, but surely not less than Ancient Rome and the Renaissance. Although Henraux was officially founded in 1821 by a Napoleonic commissioner, the history of its quarries and manufacture in Seravezza starts with Michelangelo and his well-known entrepreneurial spirit. The artist supposedly discovered the marbles in the mountains nearby and made a deal with the local community to exploit the material. Also supposedly, the deal was so unfair that the artist had to escape from Serravezza to avoid an angered crowd. Anecdotes aside, Henraux has now grown to become a leading stone company with 150 employees. It is now one of the few firms that offer totally in-house marble production from quarry to finished piece.

Although Henraux also works for large architecture and design offices worldwide, it is the collaboration with artists that has really marked its story. Important modernist sculptors such as Henry Moore and Hans Arp were loyal friends of the company, which today also sponsors contemporary art through an international prize and Fondazione Henraux. Created in 2011 by the current president Paolo Carli, the foundation is responsible for the preservation of the artistic use of this centuries old material and expertise. Milan-based curator Edoardo Bonaspetti is currently the artistic director of the foundation, which has presented or will soon present new works by acclaimed international artists such as Jenny Holzer, Neïl Beloufa, and David Horvitz.

Kunstgiesserei St. Gallen

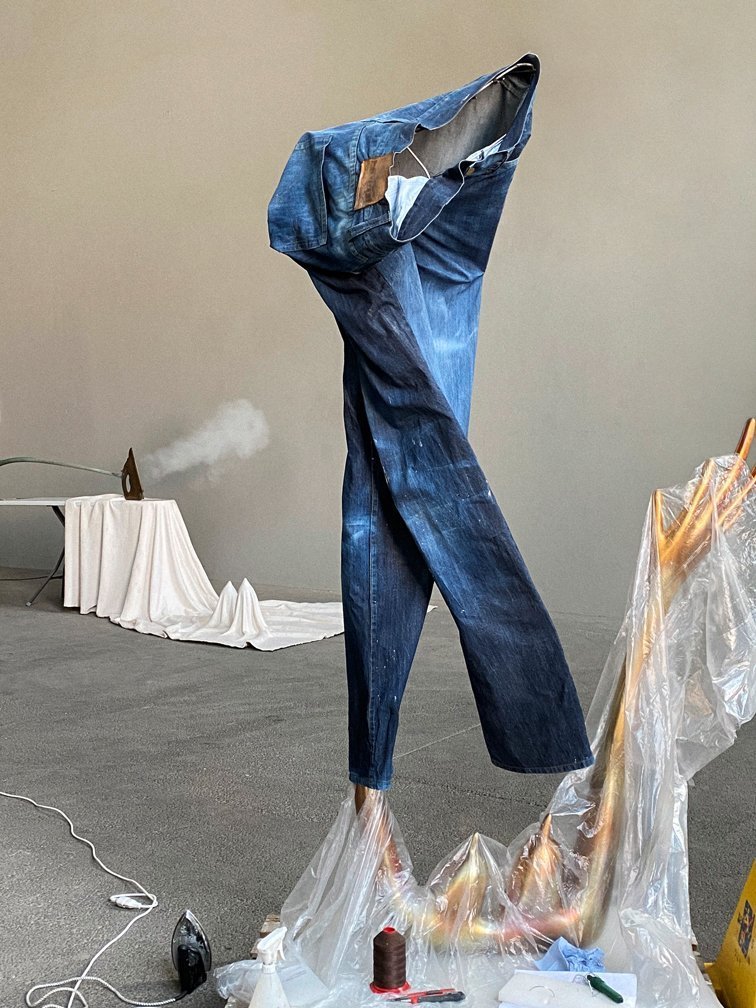

Founded in the mid 1980s in St. Gallen, Switzerland by Felix Lehner, Kunstgiesserei St. Gallen started as a small art foundry for the sculptural productions of Swiss artists. Lehner told us his first apprenticeship in an art foundry begun when he was only 13 years old, yet he later worked in an art bookshop, “not so much to become a bookseller as for the opportunity to learn about art from the books at my disposal” as he says. Among the milestones of the firm, Lehner mentions the discovery and first collaboration with the Zürich artist Hans Josephsohn, as well as the multiple productions for the artists Fischli & Weiss and Urs Fischer after the late 1990s, which also marked the opening to the international art scene.

Currently Kunstgiesserei St. Gallen employs about 60 people in their location in St. Gallen—equally divided between male and female as Lehner specifies. The firm also operates in China and it now focuses on a plethora of different techniques of metal work as well as glass, ceramics and artificial stone. The strategy for growth mentioned by Lehner is especially interesting: “We have been listening to artist’s desires in order to add more techniques and materials to our specialisations. We are now also able to combine contemporary crafts like milling synthetic materials and 3D printing with ancient techniques. All is done in-house.” Among the most important projects of Kunstgiesserei St. Gallen, Lehner mentions the production of Katharina Fritsch’s blue Hahn/Cock on Trafalgar Square, the foundation of Sitterwerk, a library and material archive for artistic research next to the foundry, as well as the growing fabrications and exchanges with Chinese artists such as Xu Zhen and Zeng Fanzhi.

Bonack

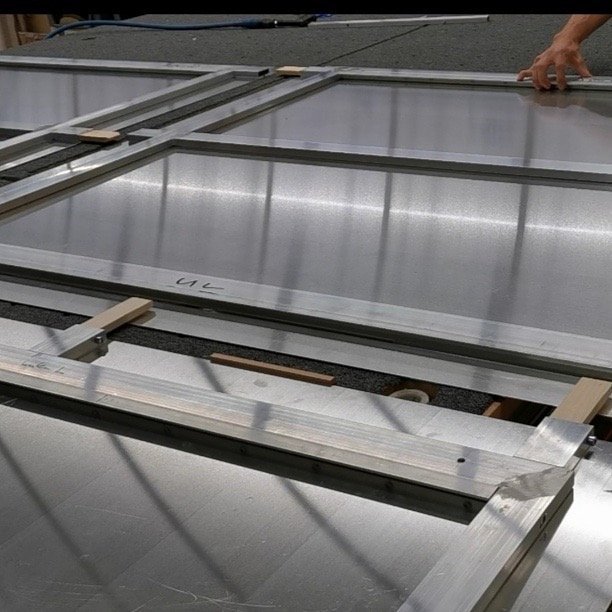

Bonack started in Berlin in 1997 as a framer and now offers other art fabrication services such exhibition displays and installation. In regards with his specialisation, the founder Hans-Jürgen Bonack rapidly understood the creative challenges of fabricating frames for artists. He told us how he believed a technical approach was overlooked in the field when he started and gave us the example of his conception of frames for the exhibition of colour studies by Josef Albers, shown between 2010 and 2012 in museums worldwide. Over the years, Bonack has worked for heavyweights in the art world including Thomas Demand, Wolfgang Tillmans, Olafur Eliasson, and Renata Lucas.

When asked about his most challenging jobs, Hans-Jürgen Bonack mentions the three pieces Black Label made for Thomas Demand. These were exceptionally large photos that stretched the limits of what could be mounted on canvas. He also recalls his work with Ai Weiwei for the piece Illumination: “It was necessary to develop a construction behind the Lego bricks which would also guarantee that an overall size of 460 x 365 cm could be hung on a wall. Moreover, the structure had to be divisible into max 4 pieces for shipping and to allow rapid assembly and disassembly with the use of a custom made fitting system.”

Berengo Studio

Adriano Berengo founded the glass making firm that bears his name in 1989 in Murano, Italy, following the model of “Fucina degli Angeli” of Egidio Costantini, a glassmaker who was able to bring international art stars to his shop in the 1950s and 60s thanks to the patronage of Peggy Guggenheim. Similarly, Berengo’s motivation to start his studio was to attract the most renowned artists for their glass productions. Among others, Berengo has collaborated with contemporary big names such as Laure Provost, Tony Cragg, Thomas Schütte, Jimmie Durham. Only in the last Venice Biennale, Berengo was able to produce glass artworks for three national pavilions.

Berengo told us that the biggest challenges today have to do with the pandemic and related travel restrictions. He says: “Although conversations can and do happen online, artists need to have the first person experience of the shop, with the smell and heat of the kilns. They need to physically be there to push the maestros toward a desired direction, becoming accomplices and learning a common language.” Among his many collaborations, Berengo is especially proud of the recent work by Ai Weiwei for the Baths of Diocletian in Rome, one of the most challenging fabrications according to him. As an ancillary project, Berengo Studio also sponsors a recurring exhibition of his productions titled Glasstress, which is held in Venice during the art biennale and around the world, most recently in Boca Raton (Florida) and at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Special Mention: Printers

When it comes to art fabricators and materials, along with the usual suspects one should also mention paper. Despite the digital age, catalogues and art books still function as a common infrastructure for information in the art world. Moreover, for some artists like Richard Tuttle or Etel Adnan, books and printed matter are also their very medium of choice. Fine printing requires technical skills just like glass blowing, bronze casting or marble carving. Many small manufacturers out there are busy achieving artistic visions on paper, often exploiting old techniques. For example, we can mention the Centre de la Gravure in La Louvière (BE) and Luciano Ragozzino in Milan (IT) for their excellent collaboration with artists, especially when it comes to artist books. At the same time, there are a few larger industrial printers that still keep an eye on quality, mostly for their production of catalogues, art and photo books. This is the case of Musumeci in Quart (IT), DZA in Altenburg (DE) and Wilco in Amersfoort (NL).

February 26, 2021